A denial of service (DoS) attack is a malicious tactic used to disrupt the normal traffic of a server, service, or network. It occurs when an attacker attempts to flood a specific target server with an overwhelming amount of requests in an attempt to crash it or cause it to malfunction. A distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack seeks to achieve a similar outcome, but does so using a large number of compromised—and often geographically dispersed—devices to make the requests that overwhelm a target server.

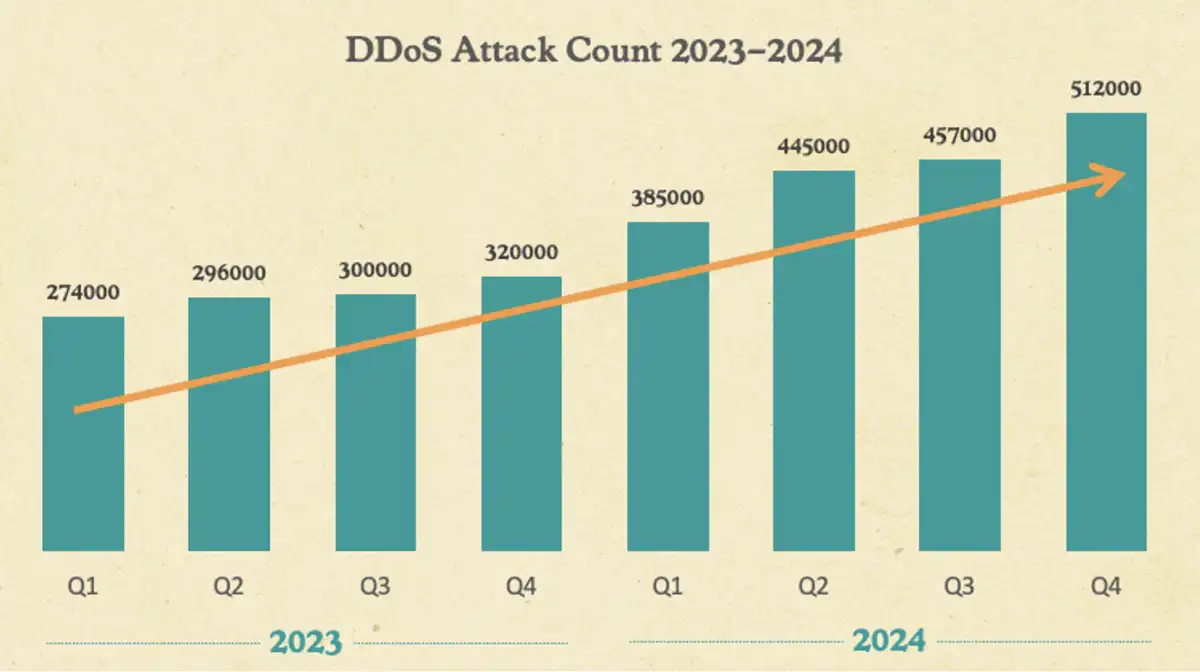

DDoS attacks, which are more challenging to mitigate based on the increased volume and distribution of traffic they introduce, have been on the rise in recent years. Gcore’s Q3-Q4 2024 Radar report that was published in February 2025 revealed a 56% year-over-year increase in DDoS attacks as compared to the same timeframe in 2023.

The scale, cost, and level of destruction associated with these attacks has also seen a dramatic increase. In June 2025, Cloudflare reported it had recently blocked the largest DDoS attack ever recorded: one that reached 7.3 terabits of data per second (Tbps). Just one month earlier, cyber security reporter Brian Krebs at KrebsOnSecurity reported an attack that reached 6.3 Tbps. And, according to Check Point’s Perimeter 81, DDoS attacks are now costing organizations approximately $6,000 per minute in downtime, averaging over $400,000 per incident for smaller organizations, with the potential to exceed over $1 million for large enterprises.

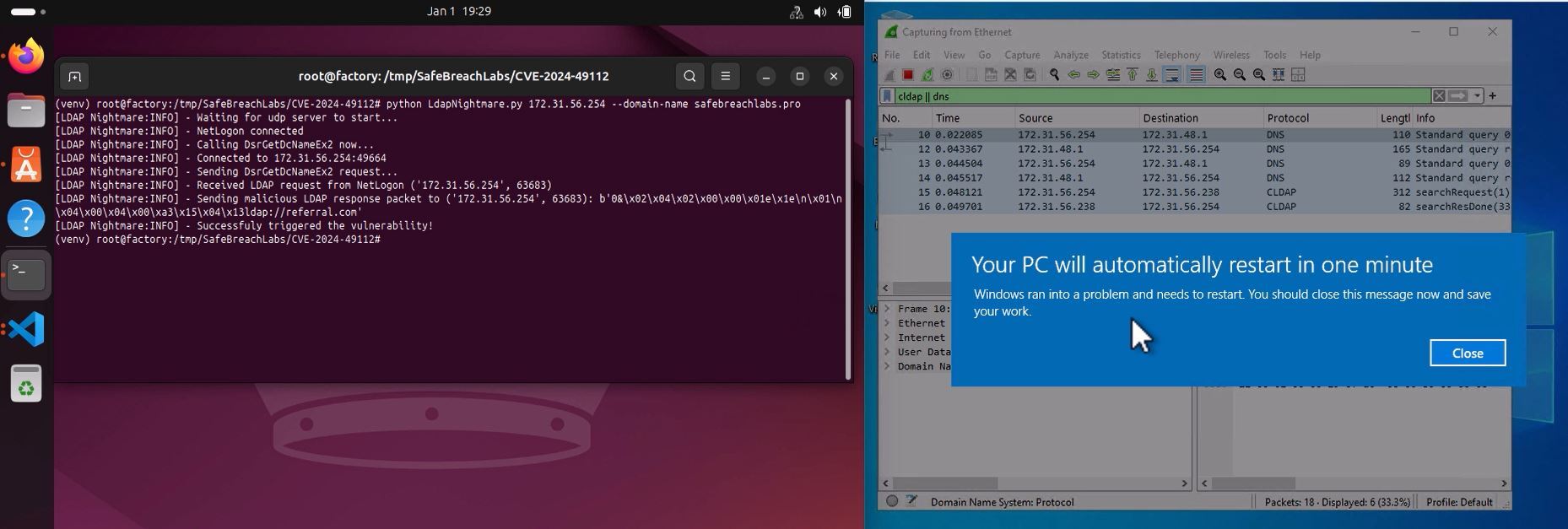

Earlier this year, SafeBreach released original research regarding a widely publicized DoS vulnerability discovered by Yuki Chen (@guhe120) called LDAPNightmare. This vulnerability—which was published as CVE-2024-49113 on the Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC) website on December 10, 2024—would allow an attacker to deny service from any unpatched domain controller (DC) by making them crash without the need for authentication or user interaction. Our LDAPNightmare research proved that despite the fact that DCs are a critical system component that have been heavily researched for security issues, blind spots that contain very simple issues can still exist in the code.

It became the basis for our latest research, which focused on identifying similar DoS vulnerabilities within developer blind spots in the Windows operating system that could be targeted and exploited. We chose to continue with DCs as the primary target based on the fact that they are a key component in most organizations’ Active Directory network—denying service of a DC in an attack could have the potential to completely halt the operations of a victim organization.

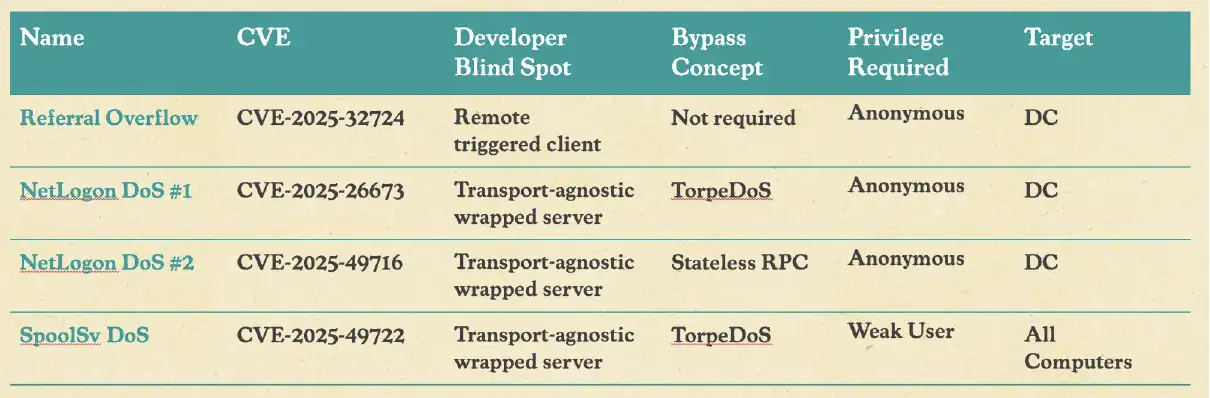

Our research focused on two potential areas where we believed developer blind spots might create new attack surfaces: client-side code and transport-agnostic wrapped server code (more on this later). Along the way, we discovered a novel DDoS technique—dubbed Win-DDoS—that could be used to create a malicious botnet leveraging public DCs, three new DoS vulnerabilities that provide the ability to crash DCs without the need for authentication, and one new DoS vulnerability that provides any authenticated user with the ability to crash any DC or Windows computer in a domain.

In the blog below, we will first provide a high-level overview of the key findings and takeaways from this research. Next, we’ll dive into our research process, outlining the technical details behind the Win-DDoS technique and the four new DoS vulnerabilities we discovered. Finally, we will highlight the vendor response and explain how we are sharing this information with the broader security community to help organizations protect themselves.

Overview

Key Findings

We set out with the research goal of identifying DoS vulnerabilities within developer blind spots in the Windows operation system that could be targeted and exploited with the potential to cause significant impact to a target organization. We focused our efforts on two key blind spots: client code and transport-agnostic wrapped server code.

Client Code

Client code expects that the server was chosen by the client and, thus, the server and the information that it returns is usually trusted. Therefore, if client code can be remotely triggered to interact with an attacker-controlled server, then we have remote client code that trusts us more than remote server code probably would.

As we explored the intricacies of the Windows LDAP client code, we discovered a significant flaw that allowed us to manipulate the URL referral process to point DCs at a victim server to overwhelm it. As a result, we were able to create Win-DDoS, a technique that would enable an attacker to harness the power of tens of thousands of public DCs around the world to create a malicious botnet with vast resources and upload rates. All without purchasing anything and without leaving a traceable footprint.

We also discovered that within the LDAP client code referral process, there are no limits on referral list sizes, and referrals are not released from the DC’s heap memory until it successfully retrieves the information from one of the servers it was referred to or if it hits the end of the referral list. By sending lengthy referral lists to DCs, we were able to widen the gap between allocations and releases so much so that LSASS crashed and forced a reboot, or a bluescreen of death (BSOD) was displayed as a result of a kernel crash, resulting in a DoS.

Transport-Agnostic Wrapped Server Code

Transport-agnostic wrapped server code is code that contains logic that is executed in order to serve client requests. However, because it is written using a framework or library that provides very good “wrapping” to all the network aspects, the developer of this code is left to only handle the application’s logic. In this case, the developer is more likely to forget about mitigating classic network related server risks.

As we tried to enumerate potential attack surfaces that contain transport-agnostic wrapped server code, we realized that remote procedure call (RPC) servers on Windows would be a perfect match. As we explored the RPC attack surface for classic server risks, we developed new techniques that highly improve the RPC call-per-minute rate. We explored different potentially vulnerable RPC functions, and found three different RPC functions that could be abused to consume too much memory on target DCs or Windows endpoints, crashing them and creating three unique DoS attacks.

The table below provides a high-level overview of each of the vulnerabilities discovered as part of our research, including the associated CVE, blind spot, bypass concept, privilege required, and target.

Takeaways

Microsoft Windows is the world’s most widely used desktop OS. This research targets some of the most valuable assets in enterprise environments utilizing Microsoft Windows—Windows DCs and infrastructure servers—whether they are exposed to the Internet or not. The vulnerabilities we discovered are zero-click, unauthenticated vulnerabilities that allow attackers to crash these systems remotely if they are publicly accessible, and also show how attackers with minimal access to an internal network can trigger the same outcomes against private infrastructure. Our findings break common assumptions in enterprise threat modeling: that DoS risks only apply to public services, and that internal systems are safe from abuse unless fully compromised. The implications for enterprise resilience, risk modeling, and defense strategies are significant.

Our research also uncovers deep and long-standing flaws in core Windows components, specifically in how RPC interfaces and the LDAP client-side behavior are implemented and secured. These vulnerabilities affect lsass.exe, spoolsv.exe, and wldap32.dll, and exploit assumptions baked into the platform: that RPC interfaces are rarely abused at scale, that LDAP clients aren’t attacker-controlled, and that internal logic doesn’t need to account for concurrency or resource exhaustion threats. We show how attackers can manipulate the Windows platform itself into becoming both the victim and the weapon, turning DCs into botnet participants without needing code execution or credentials. These findings directly challenge the security guarantees developers and defenders associate with the Windows platform and provide new insights for OS-level hardening.

Before being fixed, the vulnerabilities we have documented here could have enabled powerful cyber attacks with real-world consequences, like halting an organization’s operations, damaging critical infrastructure, impairing the functionality of medical equipment, or even being used to frame governments for cyber attacks. We believe the findings suggest several important takeaways:

- There are blind spots where basic security checks and best practices do not exist, as we might assume. If code can be triggered remotely, organizations and vendors should ensure robust security measures that prepare for worst case scenarios and resource usage. For example, in the Microsoft Remote Procedure Call (MSRPC), the most likely scenario is usually one client. However, in the worst case scenario, there could be a limitless number of clients causing an unexpected DoS. This is also true when talking about the LDAP client in DCs. Their LDAP client can be directly triggered by a remote attacker that aims to exhaust the LDAP client’s resources.

- Organizations must assume that all of their servers and endpoints can be targeted for DDoS attacks, whether they are public facing or not. In response, they should set up proper mitigations for such attacks in their infrastructure, including the ability to both defend assets and also quickly identify the source of such attacks. As we exposed, DDoS attacks can be from a single source, like our TorpeDoS.

- Servers can be turned into clients and can be leveraged by attackers to craft and present a false image of reality or, alternatively, harness resources they do not possess for malicious purposes. For example, attackers could use a Win-DDoS vulnerability to trigger DCs from a certain country to attack a different country in order to incriminate a government organization for political purposes.

The Research Process

As noted above, we set out with the research goal of identifying DoS vulnerabilities within developer blind spots in Microsoft Windows that could be targeted and exploited with the potential to cause significant impact to a target organization. We focused our efforts on two key blind spots:

- Client code: Client code expects that the server was chosen by the client and, thus, the server and the information that it returns is trusted. Therefore, if client code can be remotely triggered to interact with an attacker-controlled server, then we have remote client code that trusts us more than remote server code probably would.

- Transport-agnostic wrapped server code: Code that contains logic that is executed in order to serve client requests. However, because it is written using a framework or library that provides very good “wrapping” to all the network aspects, the developer of this code is left to only handle the application’s logic. In this case, the developer is more likely to forget about mitigating classic network related server risks.

Blind Spot 1: Client-Side Code

The first area of focus for our research was on the client code blind spot we identified as part of our original LDAPNightmare research into the vulnerability (CVE-2024-49113) originally discovered by Yuki Chen (@guhe120) in late 2024.

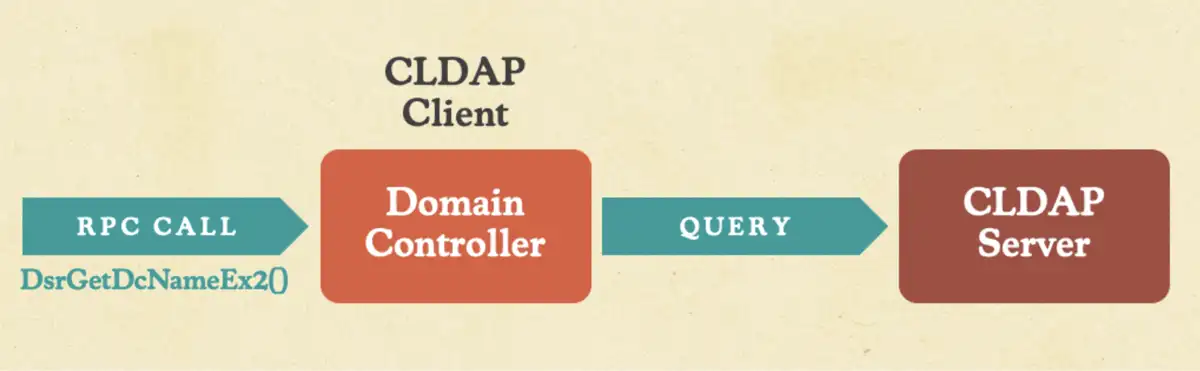

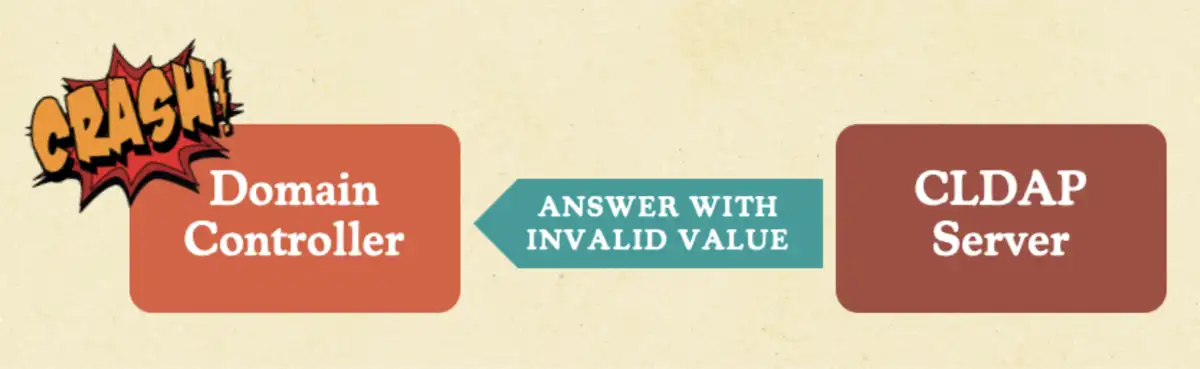

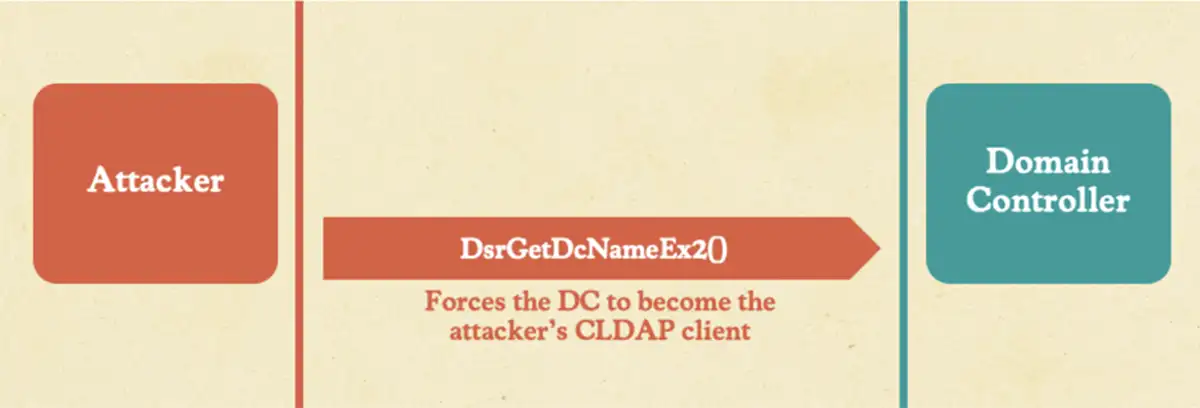

SafeBreach was the first to publish a proof-of-concept (POC) for the vulnerability, and our research revealed a specific remote procedure call (RPC) that could be executed on a domain controller (DC)—without needing to authenticate—that would allow malicious actors to turn that DC into a Connectionless Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (CLDAP) client.

The rest of the exploitation chain then returned an invalid value from the CLDAP server to the CLDAP client, which was the victim DC. This caused the CLDAP client in the DC to crash, leading the entire machine to crash as well because the CLDAP client was located in the critical process—LSASS.

From LDAPNightmare, we understood that we could turn DCs into our clients effortlessly and anonymously, as they trust any LDAP server. The client code that connects to us is the LDAP client code.

That client is implemented or, more specifically, the CLDAP client code is implemented inside the wldap32.dll, and it supports both LDAP and CLDAP. CLDAP is basically LDAP over UDP instead of TCP. The exact bug that triggered the crash was located in the LDAP client’s logic for handling referrals. The code that parses a type of LDAP packet named “referral” was flawed and crashed as a result of an invalid value in one of the packet’s specific fields.

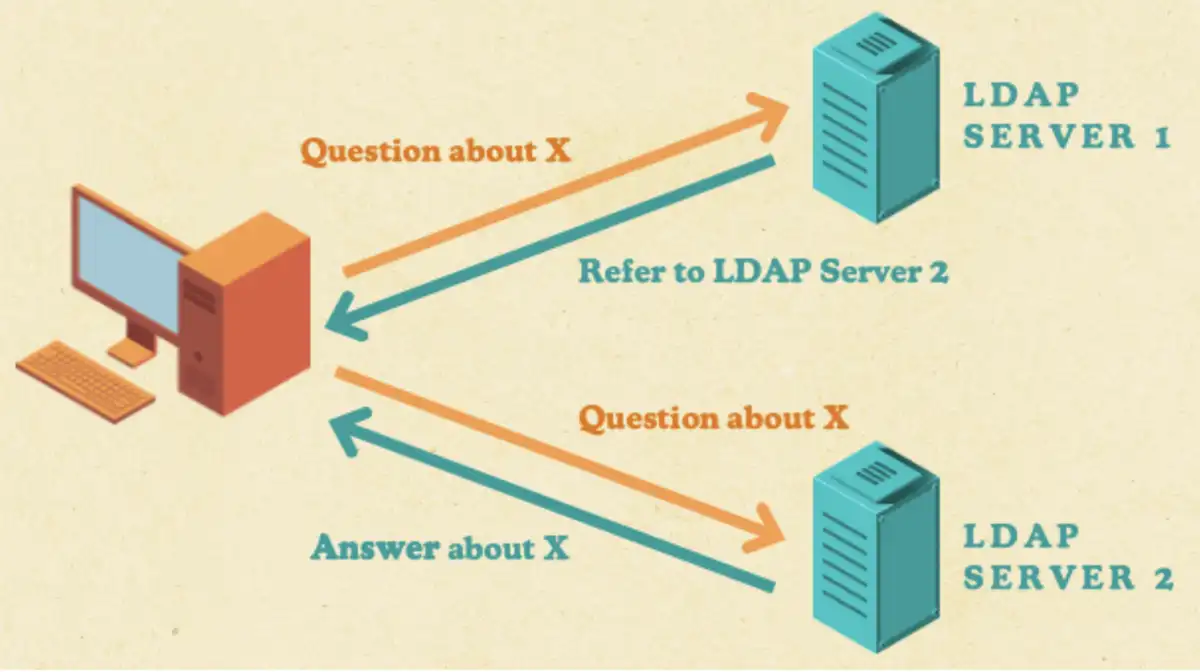

LDAP referral packets enable LDAP or CLDAP servers to refer a client to a different LDAP server in case they do not have the needed information. The client then normally chases these referrals to get the answers that it needs.

Even though the referral process didn’t really happen in LDAPNightmare and it was just an invalid field, we still learned about the referral process itself.

The Win-DDoS Attack Technique

The insights we gained about the referral process raised an important question: What if instead of returning an invalid value in the LDAP referral response, we returned a completely valid one with referrals that point to a DDoS victim? Then we might be able to trigger any DC we wanted to be a bot in a DDoS botnet attack.

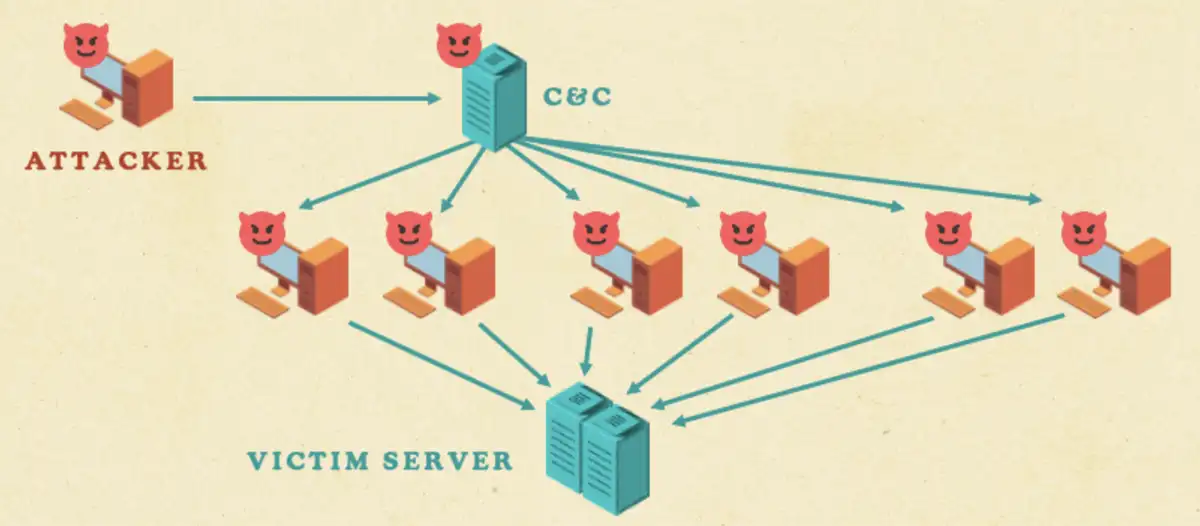

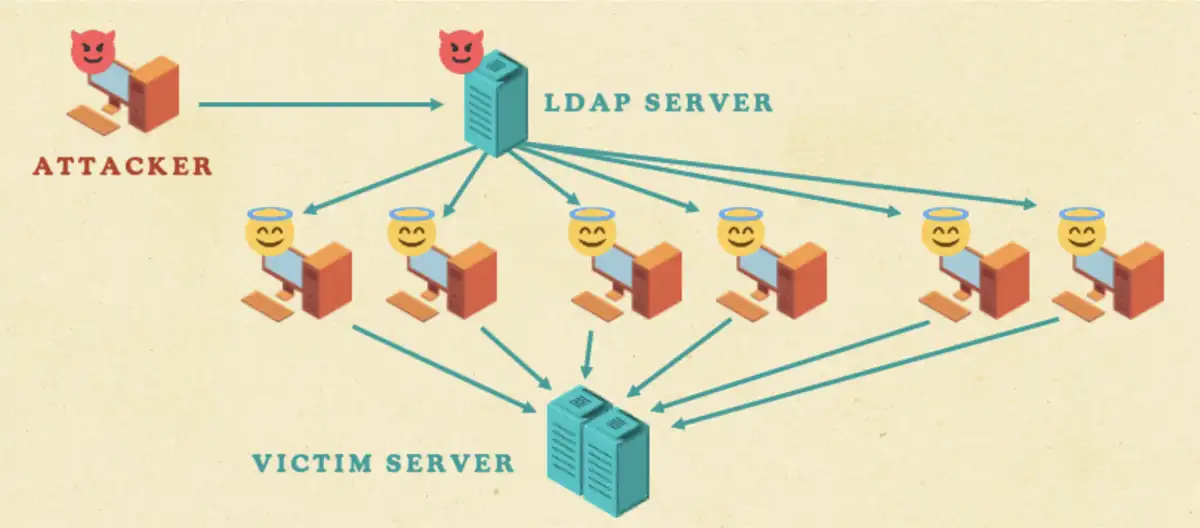

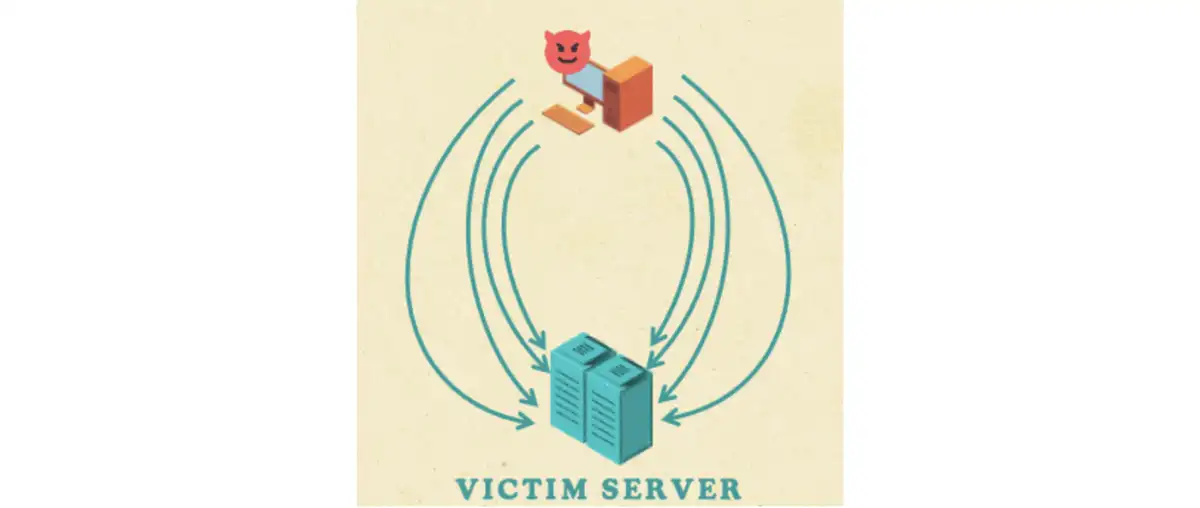

In a typical DDoS attack, an attacker must have a personal computer that initiates the attack. This computer then has to contact the server that functions as a command and control (C&C) server. This server communicates with many different bots that the attacker has already managed to compromise. And as part of this communication, the C&C server commands them to send a large amount of requests towards a single victim server in order to overwhelm it.

However, if we were able to get a large number of DCs worldwide to connect to our LDAP server and use LDAP referrals to refer them to a single victim server, we would not have to compromise other bots or have a footprint on them.

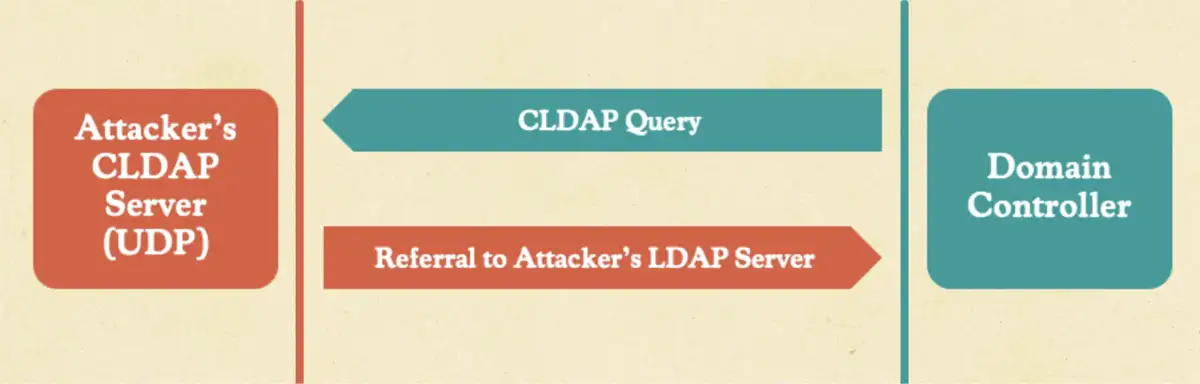

In order to supply a long list of referrals, we must first remove any size limitations. So far, the DC is connected to us via CLDAP, which is LDAP over UDP. However, UDP has a packet size limit. In order to solve this challenge, we start with the referral to our own LDAP server from the CLDAP server. When the CLDAP client in Windows receives a referral, it contacts the referral via LDAP and not CLDAP. So, we can switch from UDP to TCP. But it’s not quite that simple to provide a long list of referrals that refer to the same place.

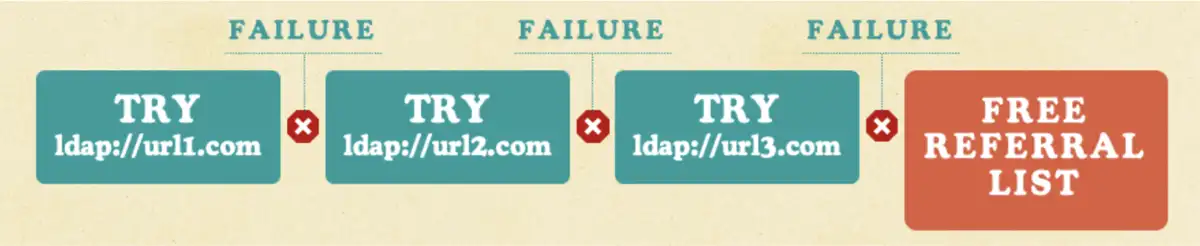

Inside wldap32.dll, which is the LDAP client in Windows, there is a function that chases referrals called LdapChaseReferral. Within that function, there is a call to a function that checks for duplicate referrals—CheckForExistingReferral(). In case the LDAP client encounters a referral that was already chased before, it stops chasing referrals and ends the process.

On the surface, it appeared that our plan might be foiled—since we would not be able to provide two of the same LDAP referral URLs, we would not then be able to flood a specific server. However, we found that even though the LDAP client validates that there are no duplicate referrals, it does that only for the URLs themselves. The client does not verify that the URLs are not resolved to the same IP.

To exploit this logic, we simply needed to configure one subdomain wildcard record in a domain that we own that leads to a victim’s IP. As a result, we’d created an innovative DDoS attack we named Win-DDoS.

The Win-DDoS Attack Flow

The attack starts with the attacker recruiting worldwide DCs by sending them the RPC call that triggers them to become CLDAP clients.

With the help of the domain that the attacker has purchased and set extra global DNS records for, the DCs then send the CLDAP request to the attacker CLDAP server. The attacker server returns a CLDAP referral response that refers the DCs to the attacker’s LDAP server in order to switch from UDP to TCP.

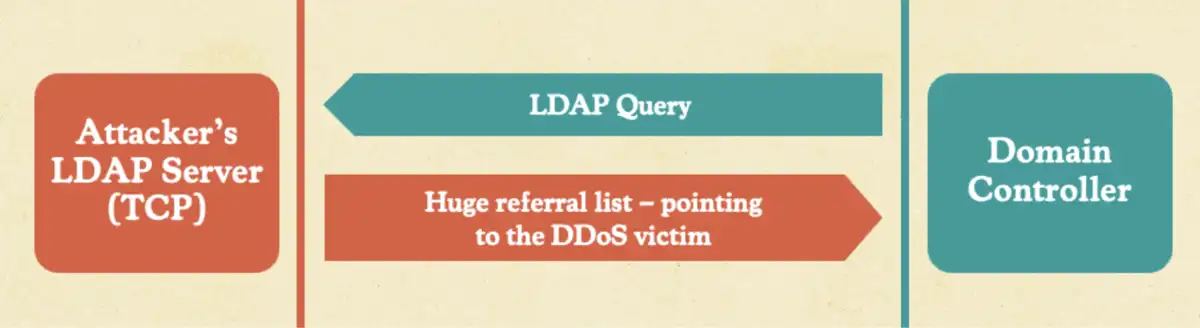

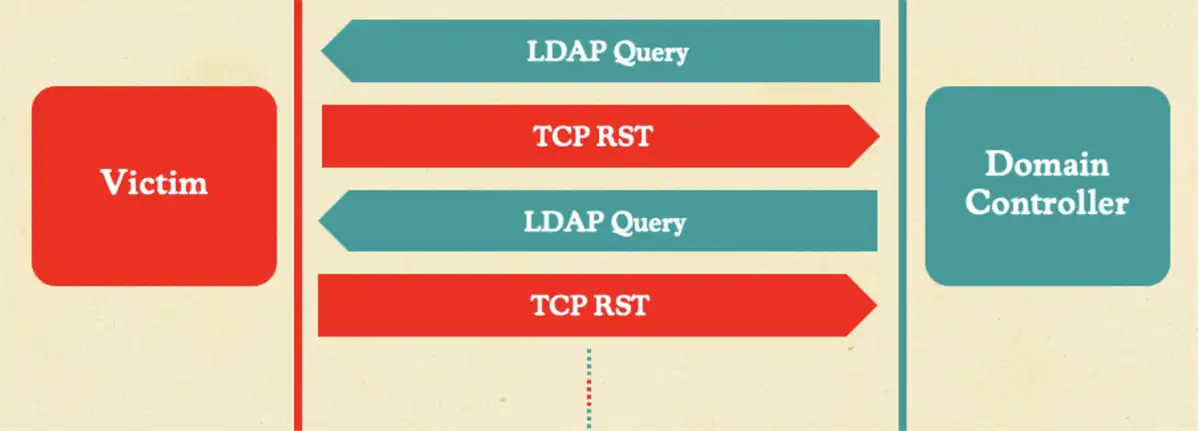

The DCs then send the LDAP query to the attacker’s LDAP server—this time over TCP. The attacker responds with an LDAP referral response containing a huge list of LDAP referral URLs, all pointing to a single port on a single IP.

The DCs then send an LDAP query to that port, and that port can be a port that serves a web server, for example. Due to the fact that web servers do not expect LDAP packets, which are not valid HTTP packets, most of them just close the TCP connection as a result. Once the TCP connection is aborted, the DCs continue to the next referral on the list, which points to the same server again. And this behavior repeats itself until all the URLs in the referral list are over, creating our innovative Win-DDoS attack technique.

We believe that Win-DDoS is an ideal DDoS attack that significantly lowers the level of effort required by attackers based on the fact that it:

- Has a very high bandwidth as it can use the power of tens of thousands of DCs around the world.

- Does not require purchasing anything.

- Does not require attackers to breach any devices, so no footprint is left on the bots.

- Can be executed from anywhere with the click of a button.

Demo

To see these capabilities in action, the following demo shows how we execute Win-DDoS in order to recruit three DCs to flood a dummy server that we created using Python.

DoS #1: Referral Overflow Vulnerability (CVE-2025-32724)

While the Win-DDoS attack we developed was significant in terms of both its impact and relative ease-of-use for attackers, we found even more to exploit in the Windows behavior we uncovered. After discovering that we could send tens of thousands of referrals, we wanted to explore whether or not there was actually a limit to the number of referrals we could send. We knew using CLDAP would limit us to send a referral list of about 64 kilobytes because it uses UDP.

Would there be a limit with TCP? As far as we tested, it did not appear that Microsoft set any limit on the referral list size or on the length of a single referral. We saw that no matter how long the list was that we sent, the LDAP client still accepted it. There were certain extremely large sizes of referral lists that we tried that simply took too much time on the attacker’s side. However, it would appear if we provided huge lists, we could eventually create huge allocations.

In addition, we discovered that the LDAP client did not release any referral URL from the list until it hit the end of the list.

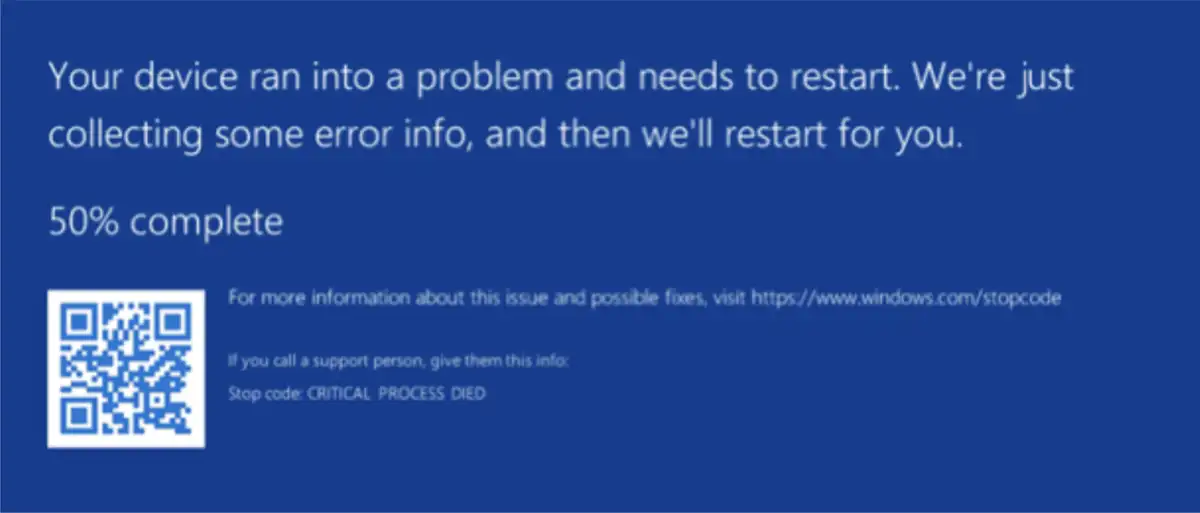

That means the longer the referral list we provided, the longer the allocation would stay in the DC’s heap memory, which could be a very long time. This widens the gap between allocations and releases. Therefore, returning huge lists of referrals—if done multiple times—would lead to yet another DoS (CVE-2025-32724) that resulted in LSASS crashing, forcing a reboot, or the BSOD.

That led us to our next idea: if we created a DoS in DCs leveraging classic server risks, we might also be able to do something similar on other attack surfaces, like the other blind spot that we mentioned—transport-agnostic wrapped server code of the RPC protocol.

Blind Spot 2: Transport-Agnostic Wrapped Server Code

As noted above, we identified what we have coined as transport-agnostic wrapped server code. This code contains logic that is executed in order to serve client requests, but is written using a framework or library that provides very good “wrapping” to all the network aspects so that the developer only has to handle the application’s logic. We found that in these cases, the developer is more likely to forget about mitigating classic network related server risks.

In search of this type of code, we began by looking at Microsoft’s definition of the RPC protocol, which is one of the building blocks of Windows. Microsoft clearly states that the RPC protocol enables developers to focus on the details of the application, rather than the details of the network. RPC is an extremely wrapped server, which seemed perfect for our use.

RPC has multiple forms of communication, and the communication is performed in the form of a server and a client. However, developers of RPC interfaces do not handle the network communication or packets. They write functions that can be called remotely and receive parameters, as if these functions were called from the same process. Our assumption was that developers are more likely to forget about mitigating classic server risks when the servers that they develop are RPC servers.

To begin, we looked for potential RPC interfaces over TCP or SMB pipes that:

- Lacked the RPC_IF_ALLOW_LOCAL_ONLY, meaning it could be accessed remotely

- Required minimal privileges and had no security callbacks, so we could access them anonymously

- Were tied to critical processes, like LSASS, to ensure crashing it would have a significant impact

We also recognized that RPC calls that consumed a lot of memory would allow us to more easily cause major damage. So, we filtered for functions with parameters that could be large in size or integer parameters that could be a large number that would lead to big allocations that would allow us to expand the gap between allocation and deallocations, making resources pile up faster.

We tried to call RPC methods that matched these criteria, but our naive approach wasn’t enough. Simply calling RPC calls that we thought would be memory consuming for a DoS attack took ages. While triggering the candidate RPC calls showed a small memory increase, it was far too slow to trigger a crash and we needed a faster way to burn through memory.

The Stateless RPC Technique

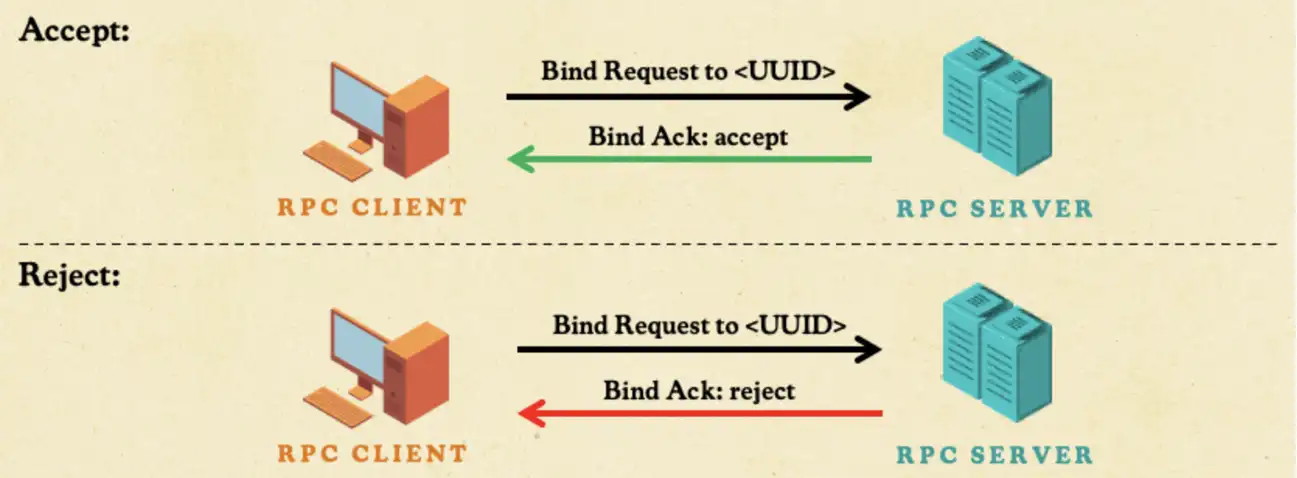

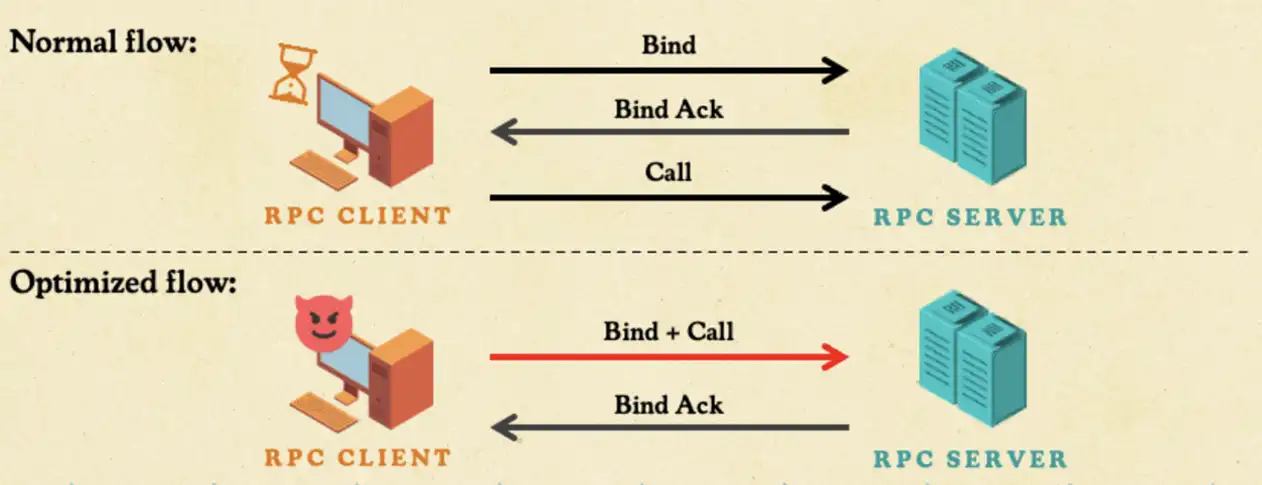

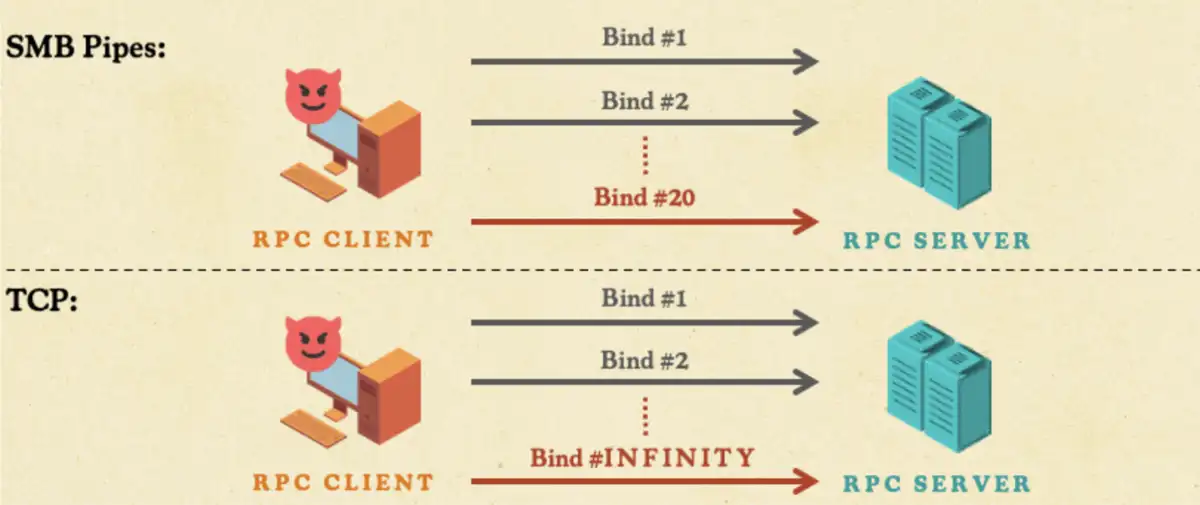

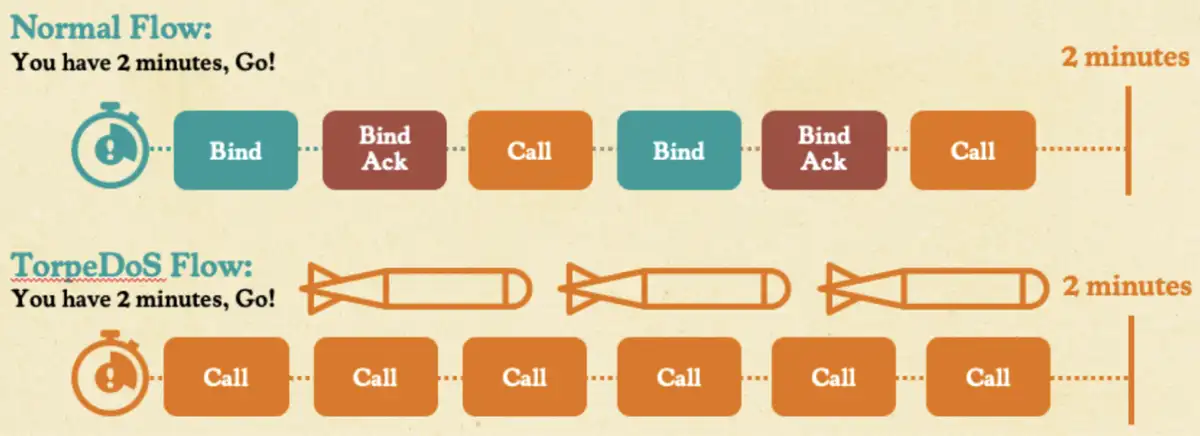

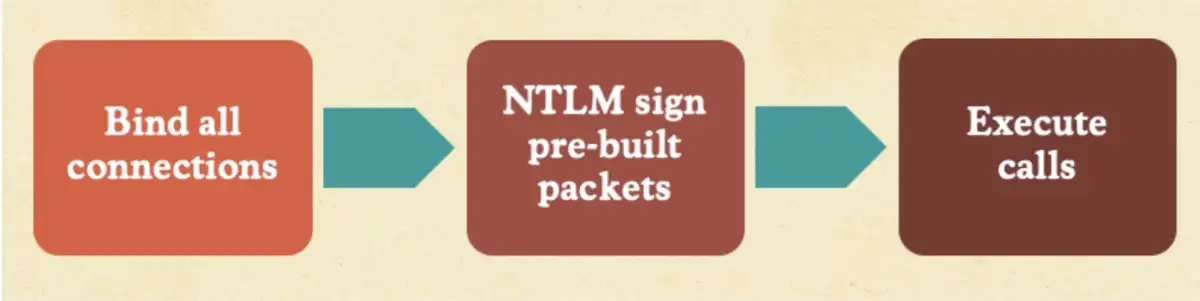

As we looked for ways to optimize our approach, we dug further into understanding the RPC insecure bind. The bind is the handshake. The client tells the server which interface it wants by sending the interface to a UUID. Then the server can accept or reject it with a bind acknowledgment.

According to the Windows RPC documentation, the client must wait for the server’s bind acknowledgment before sending the RPC call. Only after the bind acknowledgment can the client send the actual RPC call. But waiting for this process to play out wasted critical attack time.

What if we used the time to send more packets? If RPC wasn’t really stateful, we could send the bind and the RPC call together without waiting for the bind acknowledgment.

When we tested this approach, it worked—the RPC server accepted, and we discovered what we called the stateless RPC technique. This technique gave us three wins:

- First, it helped us understand that we could prebuild the RPC call packet, without the need to rebuild each time.

- Second, we were able to complete the bind and call in a single TCP packet.

- Finally, we removed the need to wait for any replies, allowing us to send the next packet right away.

The impact was remarkable. Our call-per-second rate skyrocketed and we could send the same packet repeatedly, lowering the level of effort needed by an attacker to generate a DoS attack.

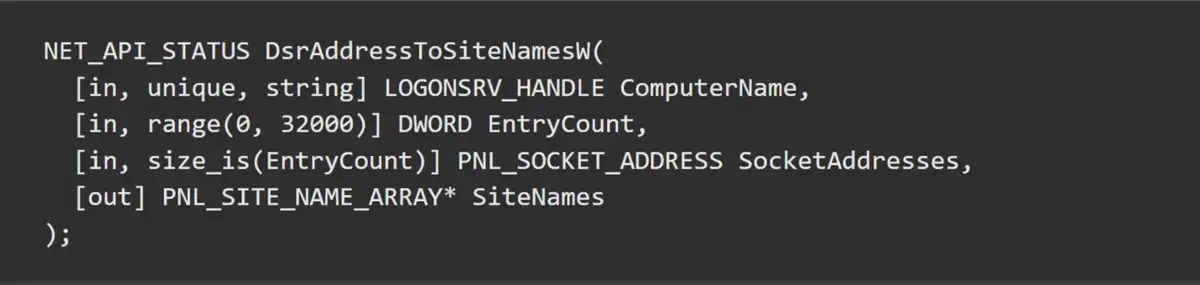

DoS #2: NetLogon Vulnerability #1 – DsrAddressToSiteNamesW Function (CVE-2025-49716)

To understand the effect of this method, we explored the DsrAddressToSiteNamesW RPC function, which is implemented inside the Netlogon RPC interface inside of LSASS. This call translates the list of socket addresses into their corresponding site names. It’s available on DCs and is unauthenticated:

The EntryCount parameter can be up to 32,000, a limit that Microsoft’s documentation said was chosen to prevent clients from being able to force large memory allocations on servers. Each call allocates at least eight times the value of EntryCount in bytes at the maximum value of 32,000 entries. That means each call can consume at least 256 kilobytes of memory.

Using our stateless RPC technique noted above, we were able to repeat this call at scale, which caused memory exhaustion due to the rapid allocations against the slower releases. As a result, we were able to crash the DC and add another unauthenticated DoS in Windows (CVE-2025-49716)—this time via RPC instead of LDAP.

However, upon further testing, we realized we couldn’t use this method in other RPC calls to successfully crash anything quickly enough. We needed another method.

TorpeDoS Technique

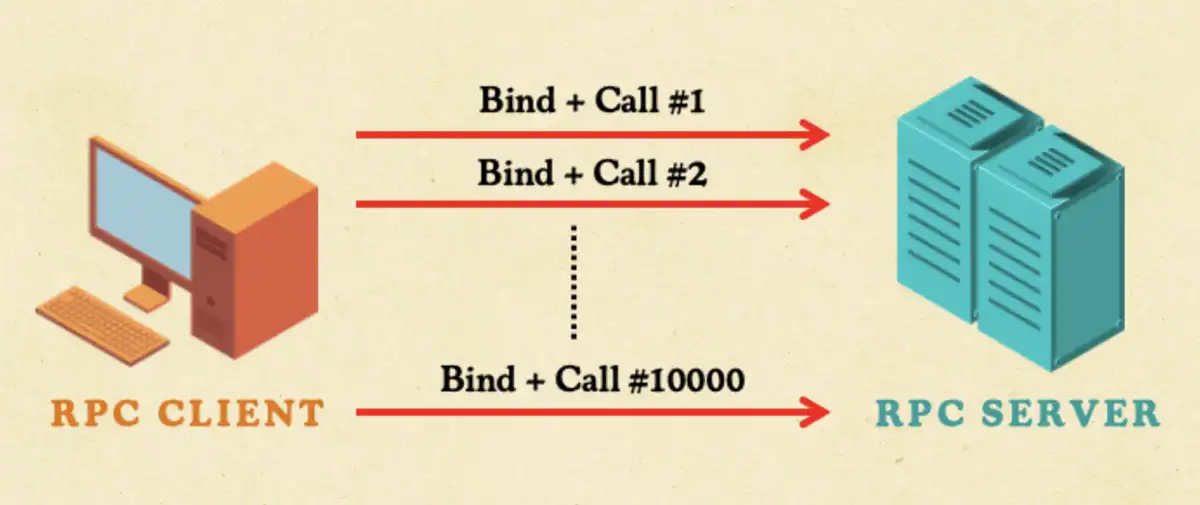

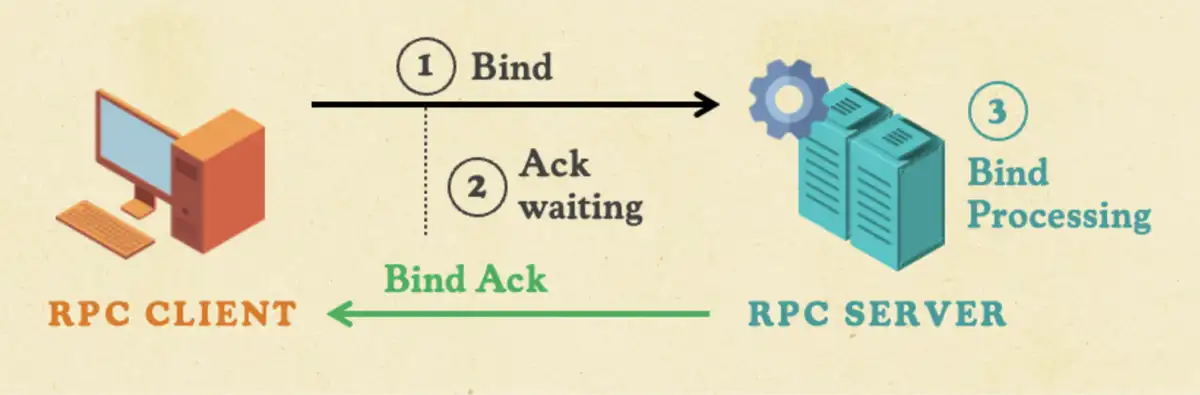

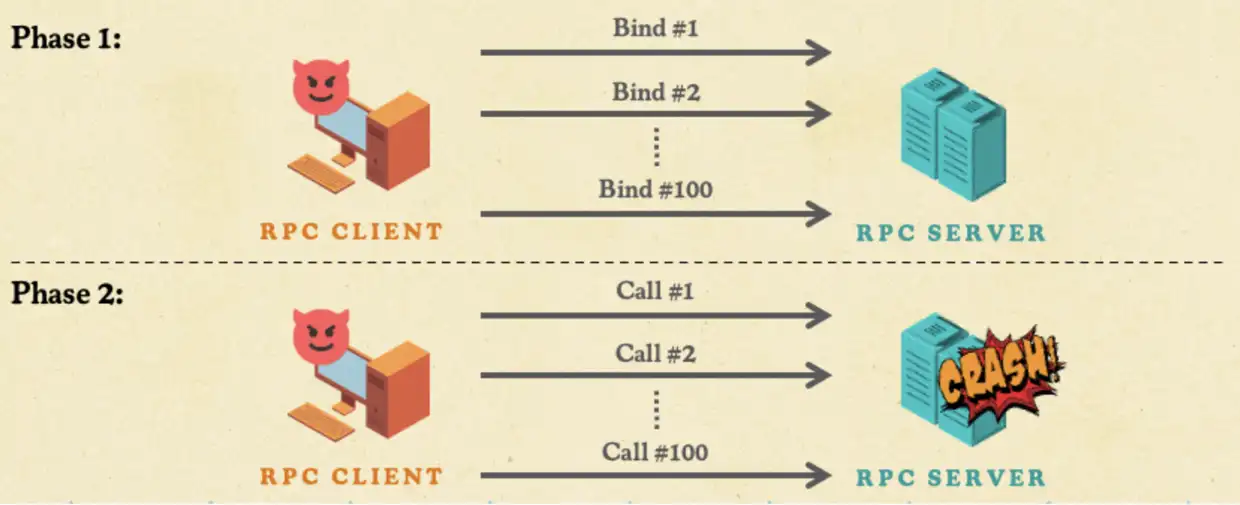

Given our discussion about DDoS attacks, we wondered if we could create a DDoS-like attack from a single machine. What stopped one computer from opening thousands of connections to overwhelm a target like a real DDoS? We believed the bottleneck that prevented this from being a reality occurred with everything before the RPC call—not just waiting for the bind acknowledgement—that simply takes too much time:

- First, sending the bind packet.

- Second, waiting for the bind acknowledgment.

- And third, the processing time of the bind packet on the target itself.

To remove this bottleneck, we decided to split the attack into two phases. Phase one would open thousands of connections by sending all the bind packets upfront from a single computer. The second phase would flood those connections simultaneously with RPC calls.

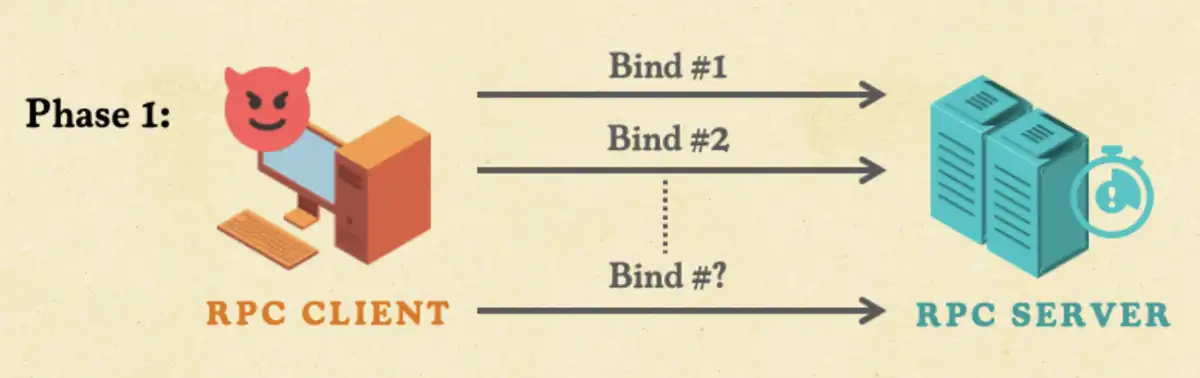

We needed to know how many bindings we could send in the first phase, since the more bind requests we could send, the more effective the attack would be. But, sending tens of thousands of bind packets from tens of thousands of connections from a single computer takes a few minutes at least. How long does the server keep those idle binds alive before dropping them?

In our tests, Windows RPC servers kept the bind-only connection open for at least up to ten minutes without timing out—we did not test any longer because it was unnecessary. This would give an attacker plenty of time to complete thousands of bindings before unleashing a flood of RPC calls. We call this technique a TorpeDoS—a single computer DDoS.

While attacking Windows machines, SMB RPC pipes enforce a strict limitation of only 20 simultaneous bindings, which significantly constrains the TorpeDoS technique. However, the TCP interfaces have no such limit—we also noticed that no common DDoS mitigations were applied to RCP calls made over TCP, like per-IP rate limiting or aggressive connection timeouts. As a result, the TorpeDoS technique became very effective.

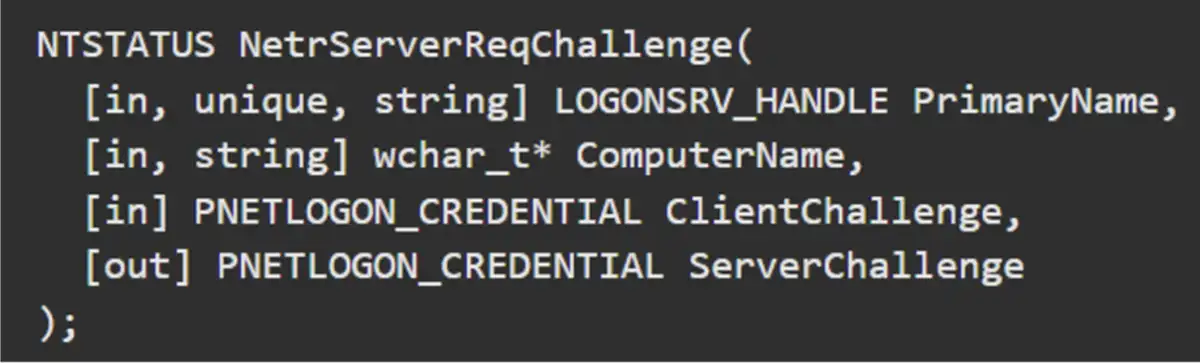

DoS #3: NetLogon Vulnerability #2 – NetrServerReqChallenge Function (CVE-2025-26673)

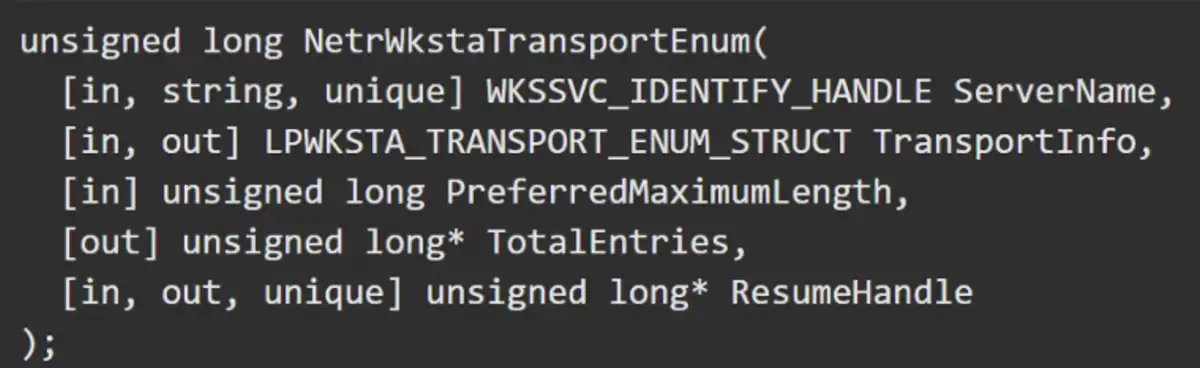

Next, we used the NetLogon RPC interface in LSASS. The following call is the first step of the secure channel session key negotiation:

This RPC call is available on DCs and is unauthenticated, meaning anyone with network access to the DC can trigger it.

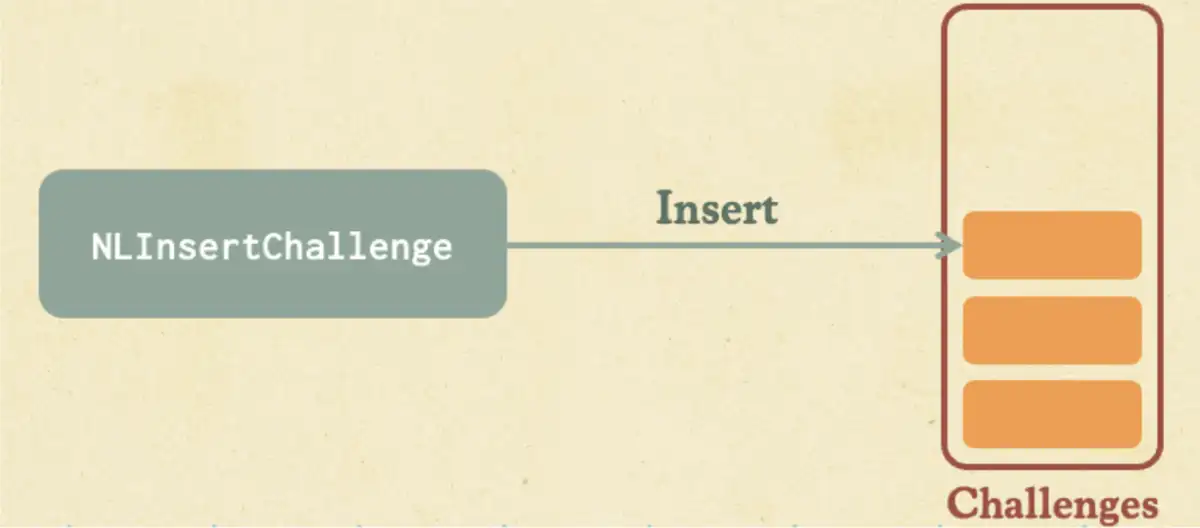

After reversing the Netlogon DLL we saw that calling this RPC triggers memory allocations via NlInsertChallenge, which saves challenges along with the ComputerName parameter that is provided to the function. This function doesn’t have input validation for this parameter, meaning we could trigger allocations with a huge amount of memory—potentially tens of megabytes of memory in a single call.

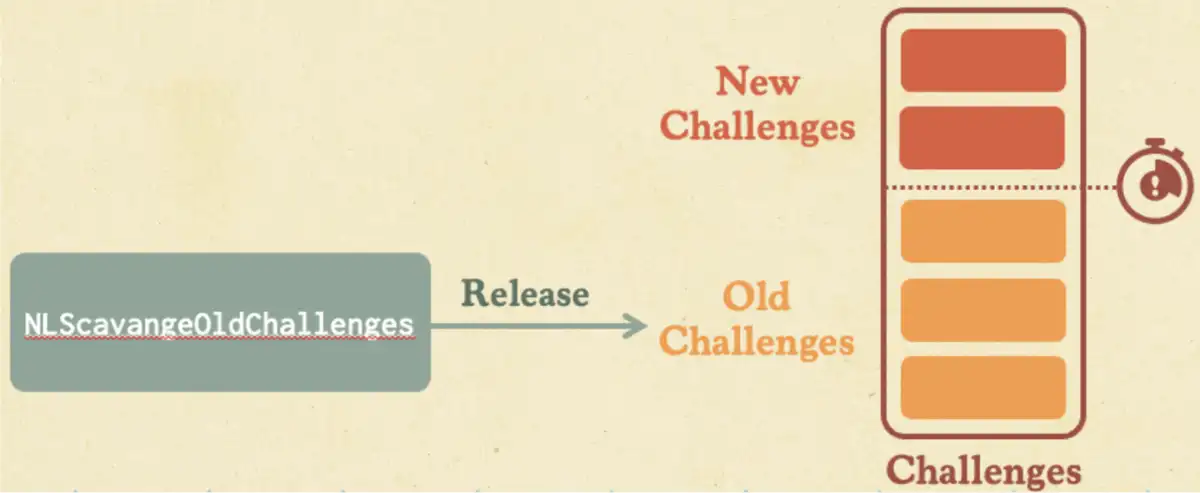

Our biggest hurdle was the logic that released previously received challenges. This is done by the NLScavengeOldChallenges function when a new challenge arrives, to “clean” old challenges that have remained in the cache for longer than two minutes.

This leaves a two minute window to crash the DC via resource exhaustion if we weren’t using the TorpeDoS technique. But since binding doesn’t create challenges, NlInsertChallenge and NlScavengeOldChallenges are never triggered if we use TorpeDoS. Using TorpeDoS, we can send a much larger number of calls in the same two minute window.

This technique provided us with the ability to exploit this short window and create another unauthenticated DoS to our arsenal: CVE-2025-26673.

Demo

To see the impact of both of the vulnerabilities that we exploited in the RPC calls, the following demo shows how we created the DoS in a victim DC.

DoS #4: SpoolSV Vulnerability – RpcEnumPrinters Function (CVE-2025-49722)

So far, we have achieved a DoS for every DC we targeted. But, what if we could crash anything, including every Windows endpoint in the domain? However, we could not find any RPC interfaces on Windows endpoints that did not require authentication. With this constraint, we decided to move on with this constraint, as crashing any computer in an active directory domain network with an unprivileged user would still be very dangerous.

One RPC call that we found in wkssvc.dll was called NetrWkstaTransportEnum. It provides details about the transport protocols currently enabled for use by the SMB network redirector on a remote computer.

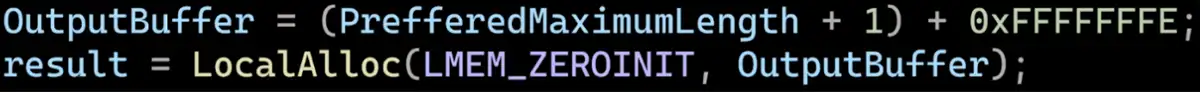

The PreferredMaximumLength parameter lets us allocate up to four gigabytes of virtual memory in one call. We don’t even need to use the TorpeDoS method here. We could force the computer to allocate hundreds of gigabytes of memory with only a few calls to this RPC. However, the victim computer didn’t crash as we expected, and we wanted to understand why.

Reversing the library shows that this function calls LocalAlloc with the size that we give it and the LMEM_ZEROINIT flag (0x40).

Using Python, we simulated the same exact call to LocalAlloc with LMEM_ZEROINIT and a two gigabyte allocation. Then we used VirtualQuery, a Windows API function that retrieves information about a range of pages to inspect the memory region, confirming it was committed with the MEM_COMMIT flag.

Microsoft’s documentation clarifies that allocating with this flag only assigns physical pages when the addresses are first accessed. That’s why we weren’t able to crash the computer—the pages weren’t accessed. Still, it confirmed our second blind spot hypothesis that a developer may overtrust RPC and forget about the potential for resource abuse.

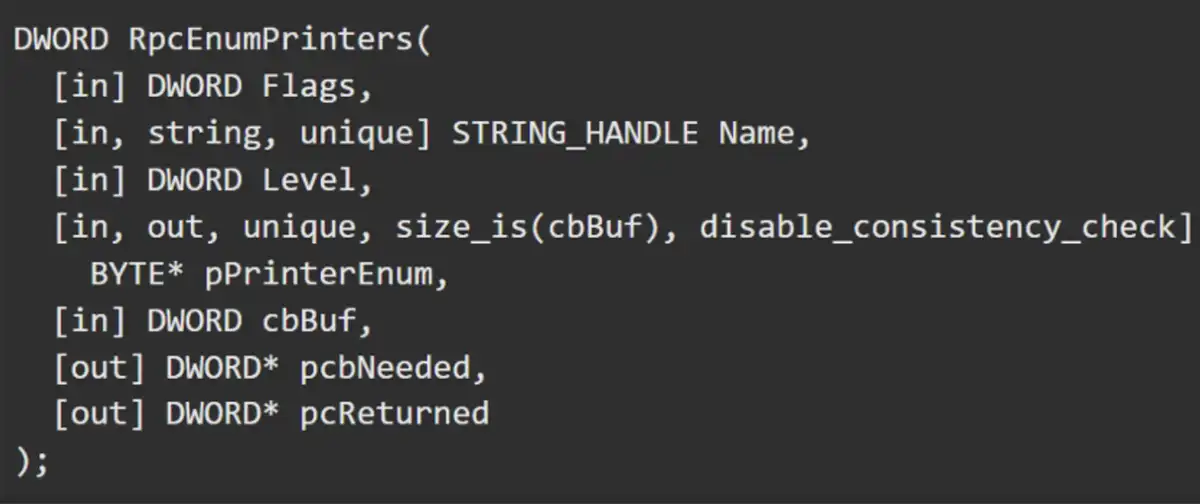

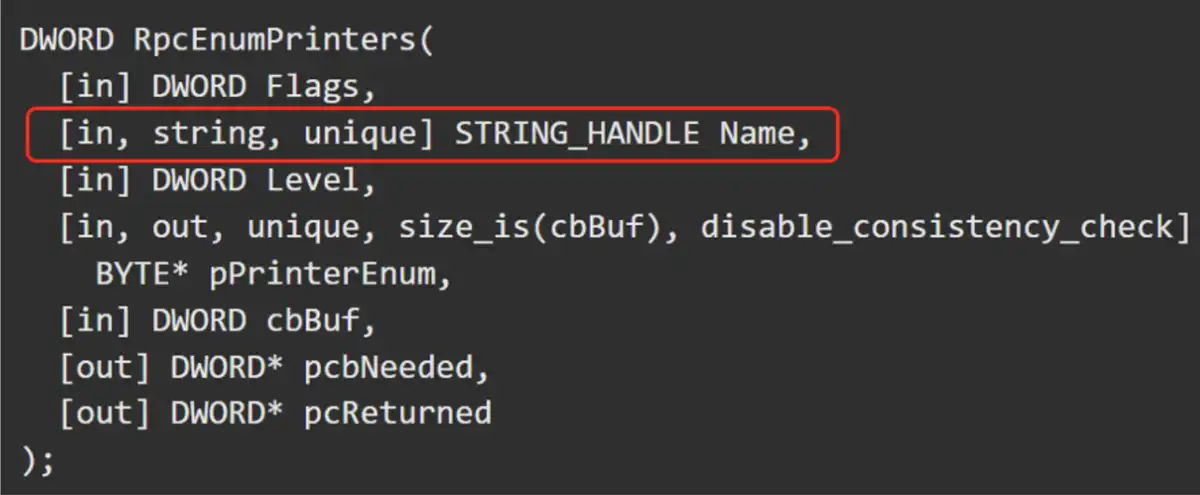

We then turned our attention to an interesting RPC function in spoolsv.exe process that enumerates available printers, servers, domains, and printer providers. As with the previous function, this function requires credentials to trigger it.

Any domain user can call it remotely on any Windows computer in the domain. However, because this call is authenticated, RPC becomes stateful. Packets after bindings are signed, and we know that signing takes time. This will break both the stateless RPC and TorpeDoS techniques we mentioned above.

But we wanted to see if we could figure out a way to use the TorpeDoS technique with authenticated calls, we sniffed with Wireshark and saw each packet was signed with NTLM and signing caused a major delay. We decided to try the following solution: pre-bind, capture the needed values for signing, then pre-sign the hardcoded packets, and only then move on to send the RPC call requests. That would restore TorpeDoS to work with authentications.

It turned out that in authenticated cases, TorpeDoS is even more relevant, since it saves more time. Using this authentication-supporting TorpeDoS technique, we once again tried to apply it to the RpcEnumPrinters function, with a long ComputerName parameter, and we managed to crash the victim Windows endpoint just as we wanted!

We’d now discovered a way for a single user to crash all Windows machines in a domain.

Demo

To see these capabilities in action, the following demo shows how we exploited the spoolsv.exe Win-DoS vulnerability to crash Windows 11.

Vendor Response

When it comes to our original research, SafeBreach is deeply committed to responsible disclosure. In line with that commitment, we notified Microsoft of our research findings in March 2025. Microsoft addressed all of the vulnerabilities we reported, and we thank them for their collaboration.

Conclusion

This research set out to explore developer security blind spots within code and how they might be exploited to enable DoS and DDoS attacks. We discovered four remotely triggered DoS attacks, whose impact began with the ability to crash a single DC and progressed to the ability to crash any Windows computer. Three of the attacks are unauthenticated, while one allows any authenticated user to crash any machine in the domain. We also discovered a novel technique to create a botnet of world-wide public DCs that would enable a DDoS attack.

To help mitigate the potential impact of the vulnerabilities identified by this research, we:

- Responsibly disclosed our research findings to Microsoft in March 2025, as noted above.

- Shared our research openly with the broader security community here and at our DEF CON 33 (2025) presentation to enable the organizations and end-users leveraging the Windows OS to better understand the risks associated with these vulnerabilities.

- Have provided a GitHub research repository that includes the tools and exploits discussed within this research to serve as a basis for further research and development.

For more in-depth information about this research, please:

- Contact your customer success representative if you are a current SafeBreach customer

- Schedule a one-on-one discussion with a SafeBreach expert

- Contact Kesselring PR for media inquiries

About the Researchers

Or Yair (@oryair1999) is a security research professional with more than seven years of experience, currently serving as the Security Research Team Lead for SafeBreach Labs. Or started his professional career in the Israel Defense Force (IDF). His primary focus lies in vulnerabilities in Windows operating system’s components, though his past work also included research of Linux kernel components and some Android components. Or’s research is driven by innovation and a commitment to challenging conventional thinking. He enjoys contradicting assumptions and considers creativity a key skill for research. Or has already presented his vulnerability and security research discoveries internationally at conferences such as Black Hat USA, Europe, and Asia, DEF CON, SecTor, RSAC, Recon, Troopers, Sec-T, BlueHatIL, Security Fest, CONFidence, and more.

Shahak Morag (@ShahakMo) has over seven years of experience in security research and is currently serving as a Research Lead at SafeBreach. His background includes extensive expertise in Linux kernel and embedded systems, with more than a year of focused research on Windows platforms.