The remote procedure call (RPC) protocol is one of the building blocks of Microsoft Windows and is widely used for inter-process communication between clients and servers. When RPC clients search for a server based only on a universally unique identifier (UUID) of an interface—without specifying an endpoint—they will go through the Endpoint Mapper (EPM). It will connect them to an endpoint that a server registered, exposing the interface the clients are looking for.

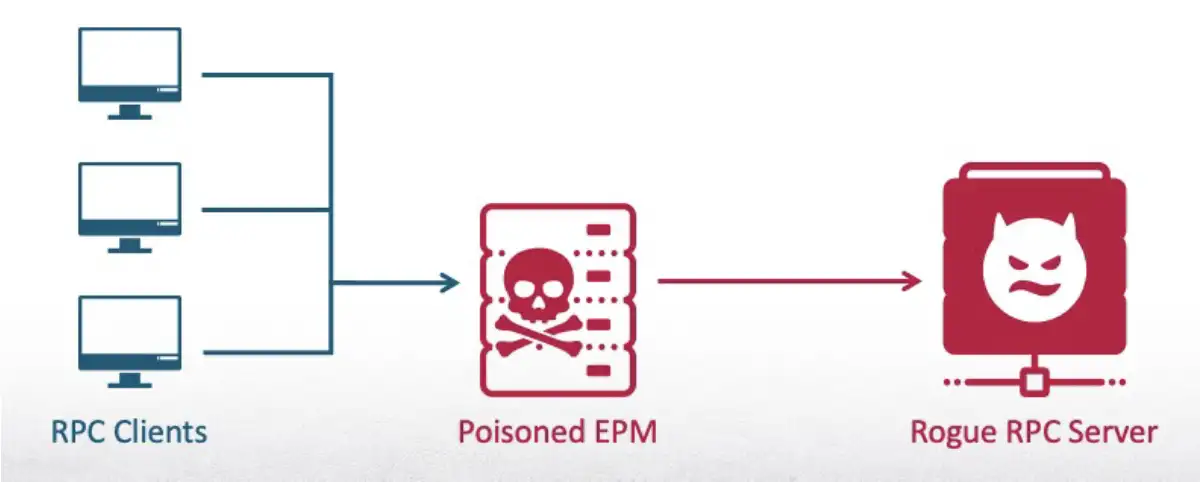

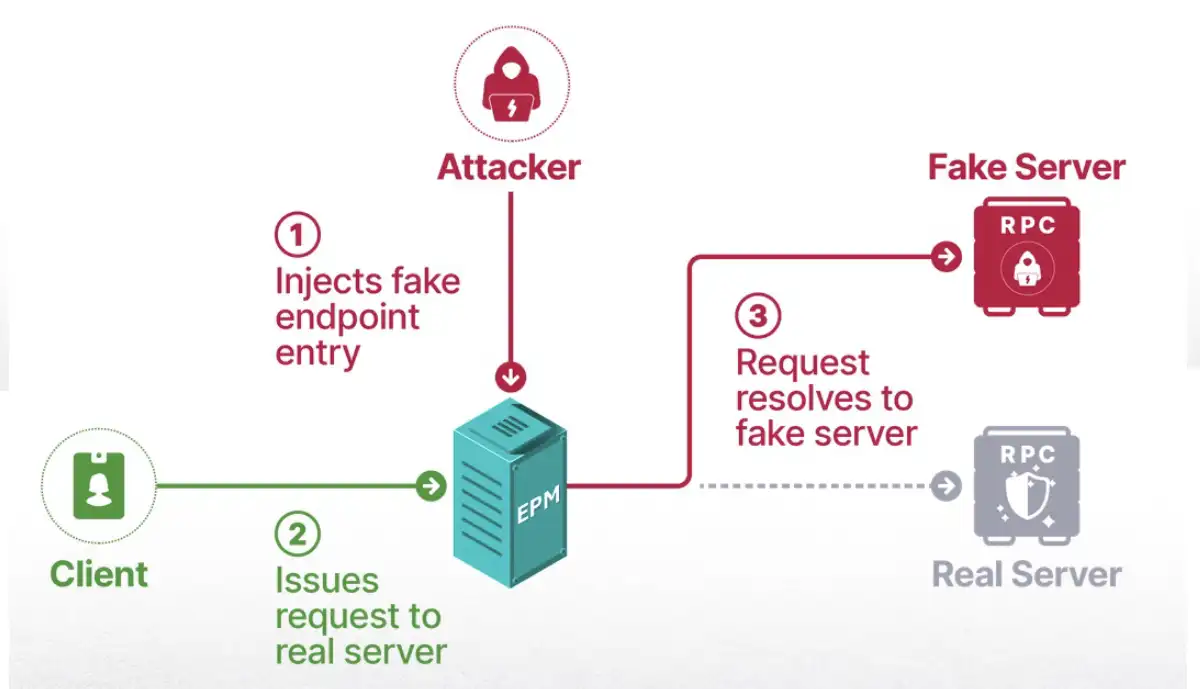

In this way, an EPM behaves very much like a DNS server and resolves a UUID to an endpoint. Based on my understanding of the RPC protocol and the EPM, I set out to understand whether an attack like DNS poisoning—which manipulates DNS data to redirect users to malicious websites—could be applied to the EPM. During this process, I discovered a significant vulnerability that allowed me to manipulate a core component of the RPC protocol to bring my new “EPM poisoning” technique to life. The vulnerability—and the techniques I developed to exploit it—had the potential to create devastating results if used by a malicious actor.

In the following blog, I’ll first provide a high-level overview of the key findings and takeaways from this research. Next, I will explain details of the RPC protocol, including the definition of some basic terms. Then, I’ll show how I was able to manipulate a core component of RPC and masquerade as a legitimate, built-in service to force a protected process to authenticate against an arbitrary server and disclose the NTLM hash of the machine account. I will also highlight the vendor response and describe several detection capabilities organizations can enact to protect other clients and interfaces that might be vulnerable to this type of attack. Finally, I’ll explain how I am sharing this information with the broader security community to help organizations protect themselves.

Overview

Key Findings

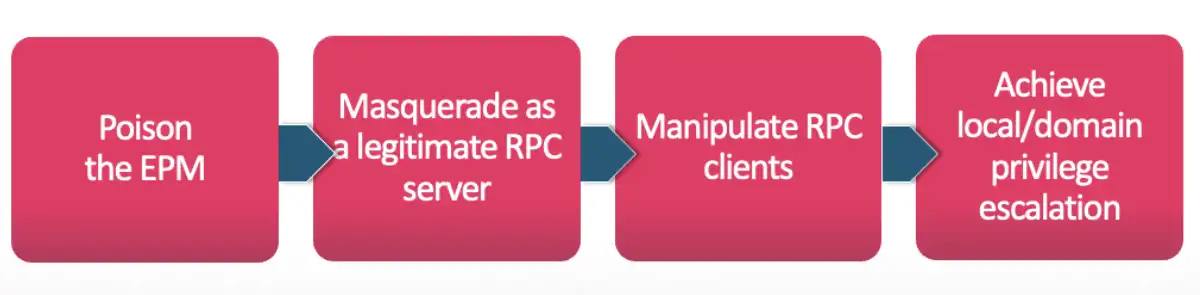

I set out with the research goal of seeing whether I could map a UUID of a trusted RPC interface to an endpoint that I controlled, leading to my own malicious RPC interface. I quickly discovered a serious security issue in a core component of the Windows RPC protocol. Specifically, this vulnerability revealed that there was no verification process to stop unprivileged users from posing as a well-known RPC server.

However, to have clients connect to me, I needed to register with the EPM first before the original services of the RPC interfaces did. I examined the status of RPC servers at certain points during boot and mapped several interfaces that could be abused. I then attempted to “race” their services to register and, as a result, was able to get various high integrity processes—and even some protected process light (PPLs)—to trust me to be their RPC server.

With this knowledge, I developed RPC-Racer—a toolset that could be used to find insecure RPC services and—in this example—maniplulate a PPL process to authenticate the machine account against any server I wanted (CVE-2025-49760).

Takeaways

The implications of this research are significant not only to Microsoft Windows—which is the world’s most widely used desktop OS—but also to other OS vendors that may have similar vulnerabilities. We believe the findings suggest several important takeaways:

- The integrity of servers should be checked every protocol. Just like SSL pinning verifies that the certificate is not only valid but uses a specific public key, the identity of an RPC server should be checked. The current design of the endpoint mapper (EPM) doesn’t perform this verification. Without this verification, clients will accept data from unknown sources. Trusting this data blindly allows an attacker to control the client’s actions and manipulate it to the attacker’s will.

- There is an inherent danger in setting services to delay start, and software developers of RPC servers should be aware of the implications of launching their applications late in the boot process. Services are often set to delay starts to make the boot process faster, but performance cannot come at the expense of security. Any stage where untrusted code can be executed should be considered unsafe.

Background on the RPC Protocol

The RPC protocol in Microsoft Windows is used for inter-process communication between clients and servers. The server exposes functionalities—certain actions and logics—and the client can request that the server executes them on its behalf. The server can run on the same machine as the client or on another computer in the network.

Both RPC clients and servers use an interface definition language (IDL) file that contains the properties of the RPC interface, like definitions of structs, enums, functions, and—most importantly—the universally unique identifier (UUID). This identifier is used by the server when it registers to the machine and used by a client when it looks for its server.

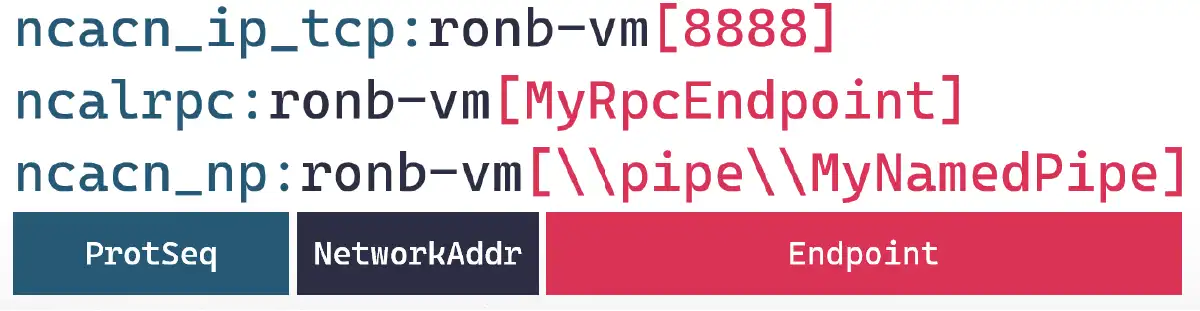

Before a client can communicate with a server, it first needs to create a binding handle, which is composed of three parts:

- The protocol sequence, which determines which protocol will encapsulate the RPC communication. The three most common protocols are TCP, named pipes over SMB, and the advanced local procedure call (ALPC). This protocol is used to transfer messages efficiently and securely between processes running on the same machine only.

- The network address, which can be an IP address or computer name.

- The endpoints, which are different for every protocol sequence. For TCP, it is the port number. And for SMB, it is the name of the pipe. For ALPC, it is a unique string for that server—two RPC servers cannot have the same endpoints.

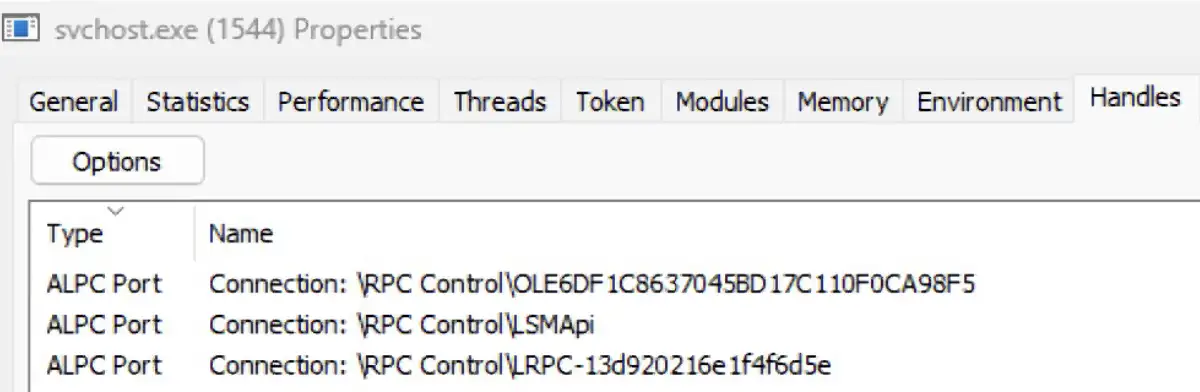

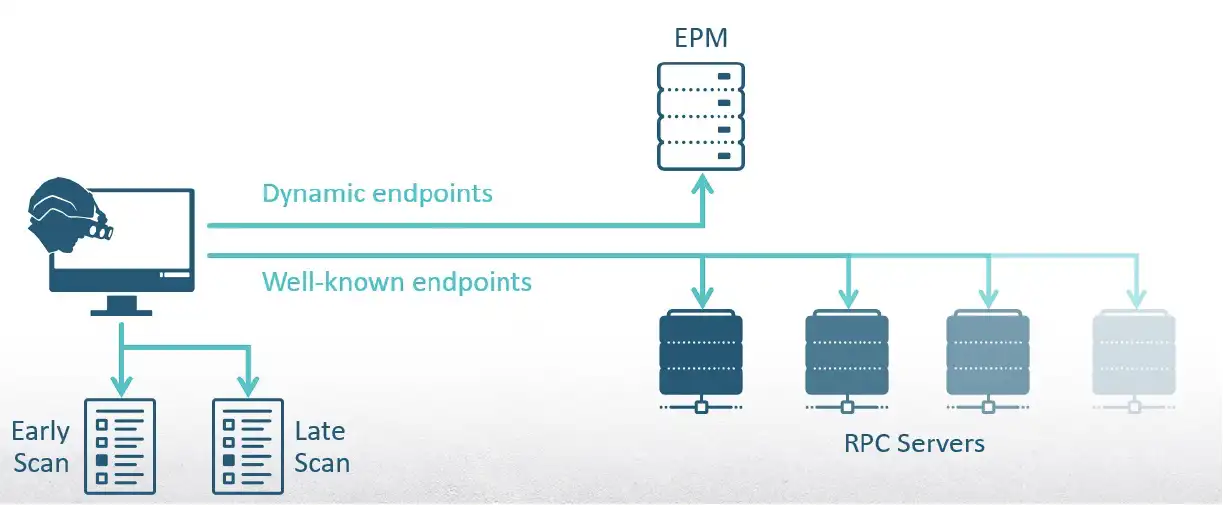

For the purpose of this research, we will focus on the meaning of endpoints for ALPC. When a server registers itself, it can either specify an endpoint or not. If it does, then the communication with it would be based on a well-known endpoint. The client has a hard coded string that it knows will match the server. If the server doesn’t register with an endpoint, a unique stream will be generated for it instead. This is called a dynamic endpoint. In the image below, we can see three endpoint names.

The first name, which starts with OLE, is a unique string with generated characters, even though it isn’t the dynamic endpoint we are talking about. It refers to endpoints that are related to distributed COM objects and are irrelevant for this discussion. The second name, which is LSMApi, is a well known endpoint that is registered by the local session manager. The third name, which starts with LRPC, refers to endpoints that are dynamic and contain generated characters.

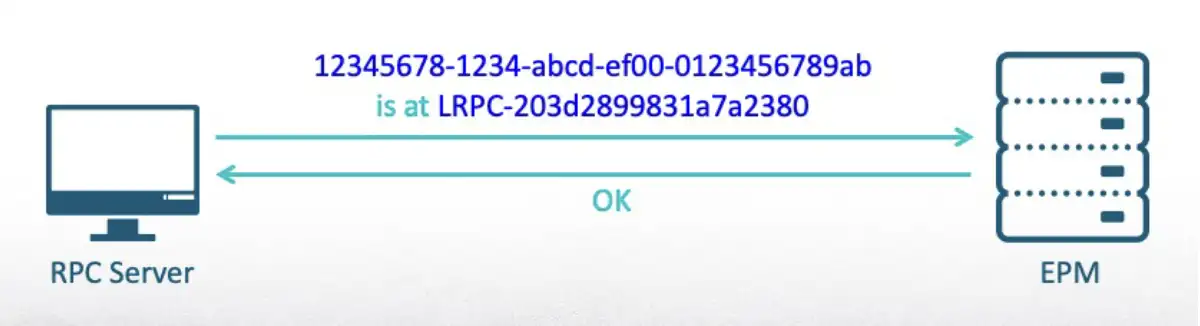

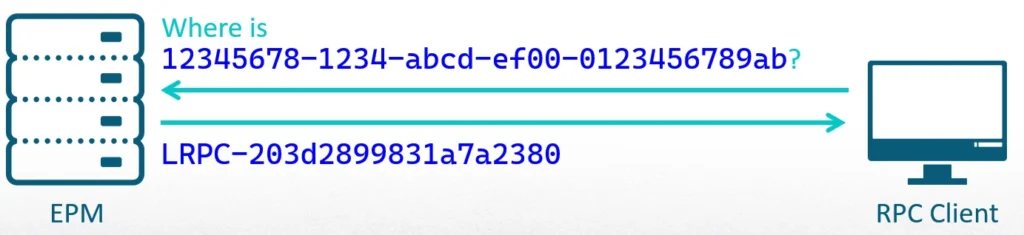

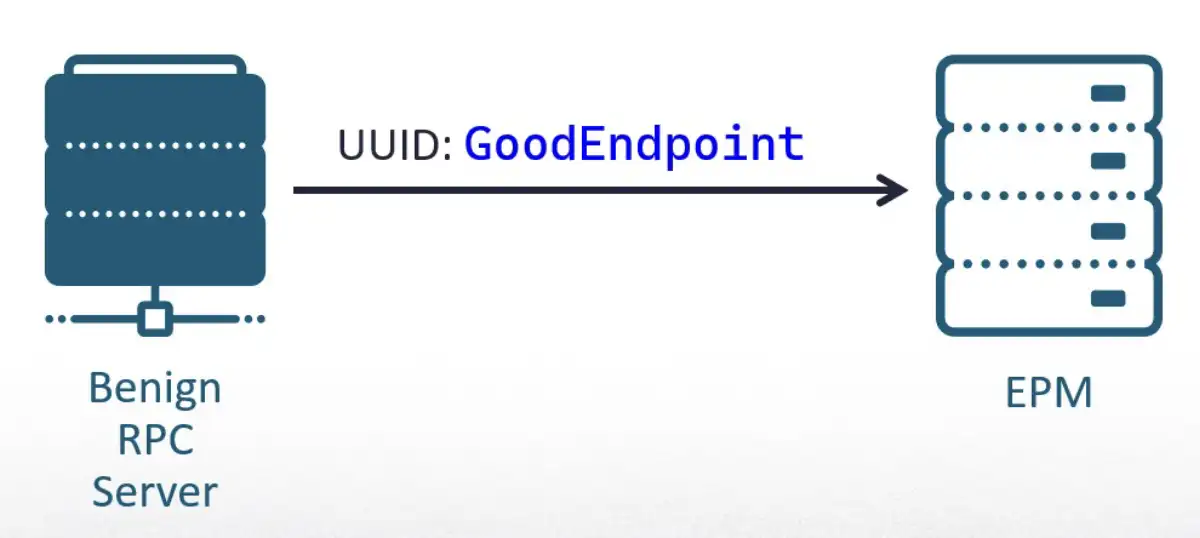

The question is: If a dynamic endpoint is random, how does the client know who to communicate with? This is where the endpoint mapper (EPM) comes in. The EPM maps between an interface UUID and the endpoints that expose it. If a server decides to use a dynamic endpoint, it needs to make sure it can be found by its clients. It does this by registering to the EPM.

After the registration, the client will be able to establish an RPC connection using only a UUID. The EPM will connect it to the first server that registered that interface.

There are two important rules the EPM follows:

- First, entries can be removed only if the original process unregisters or terminates.

- Second, the EPM will always use the first endpoint registered for an interface. The order cannot be modified.

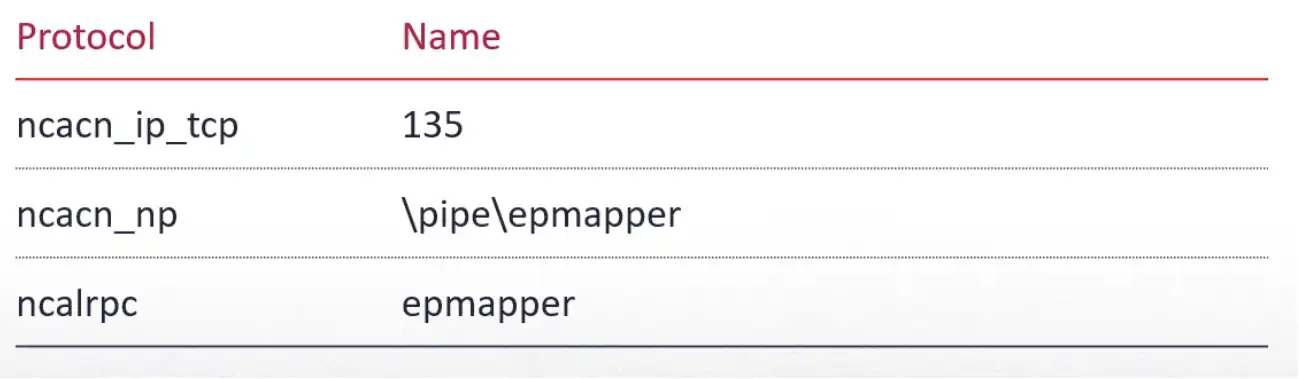

The EPM is managed by the DLL RpcEpMap function, which is loaded by the service RpcSs. Once it is loaded, it can be reached using multiple protocols: TCP, named pipes over SMB, and ALPC. Each one has its own known endpoint.

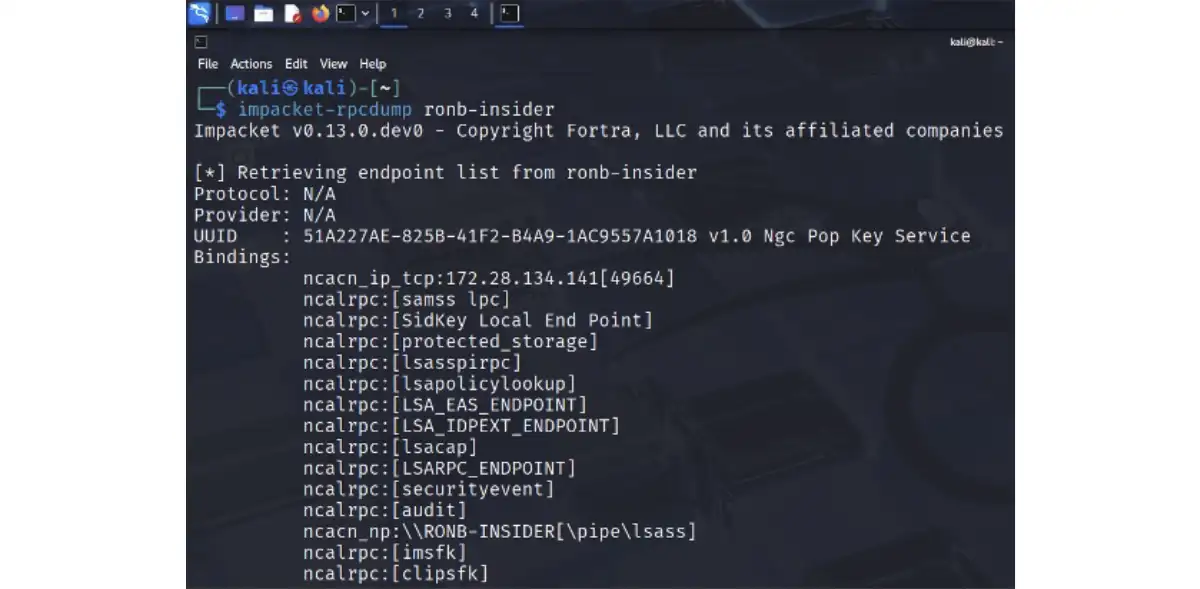

The EPM can be queried locally or remotely using tools like rpcdump from Impacket, as shown below. The EPM behaves very much like a DNS server and resolves UUID to an endpoint.

The Research Process

Based on my understanding of the RPC protocol and the EPM, I developed an idea. Could an attack like DNS poisoning—which manipulates DNS data to redirect users to malicious websites—be applied to the EPM? Could I masquerade as a legitimate RPC server and have clients connect to me instead of a real one, creating a new EPM poisoning attack?

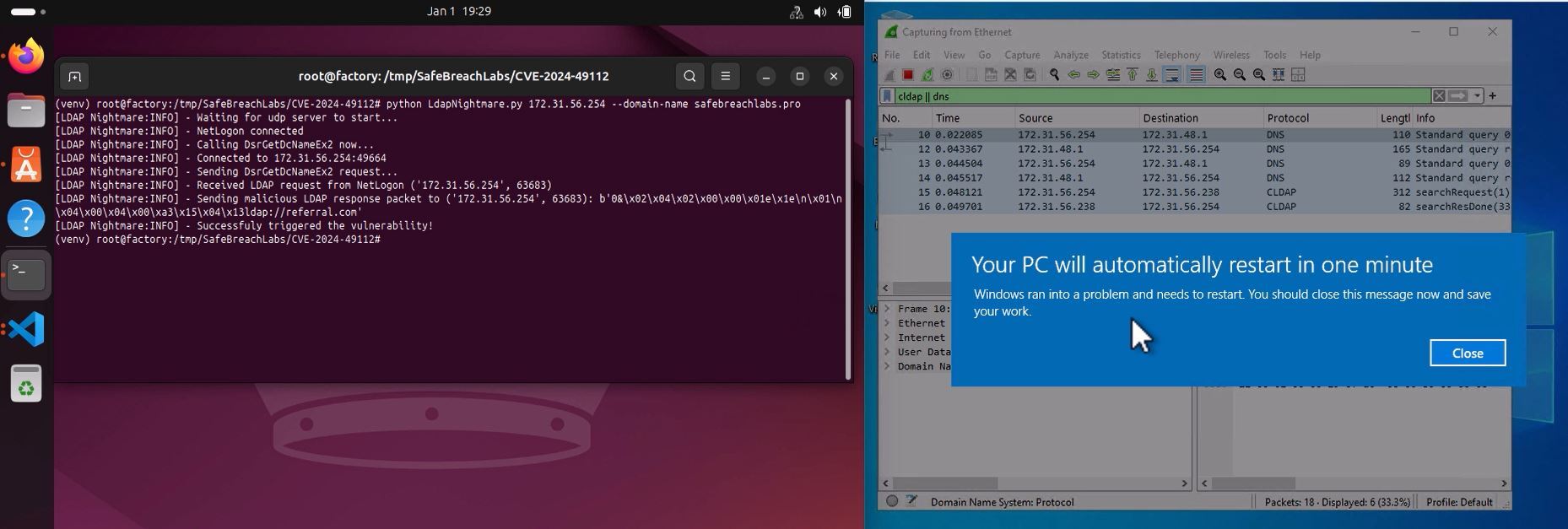

Looking back at famous RPC exploits—like PrintNightmare and PetitPotam—we see they usually targeted vulnerable code in servers to achieve remote code execution (RCE) or privilege escalation. But vulnerable code exists in RPC clients as well and that, I decided, would be the target of my research.

To achieve my goal, I would first need to figure out how to poison the EPM. Once the EPM was directed to forward RPC connections to me, I would need to act like a legitimate, built-in service and send a malicious response to clients that would help me achieve privilege escalation. Our starting point for this attack is running without administrator privileges, as a medium integrity process.

Poisoning the EPM

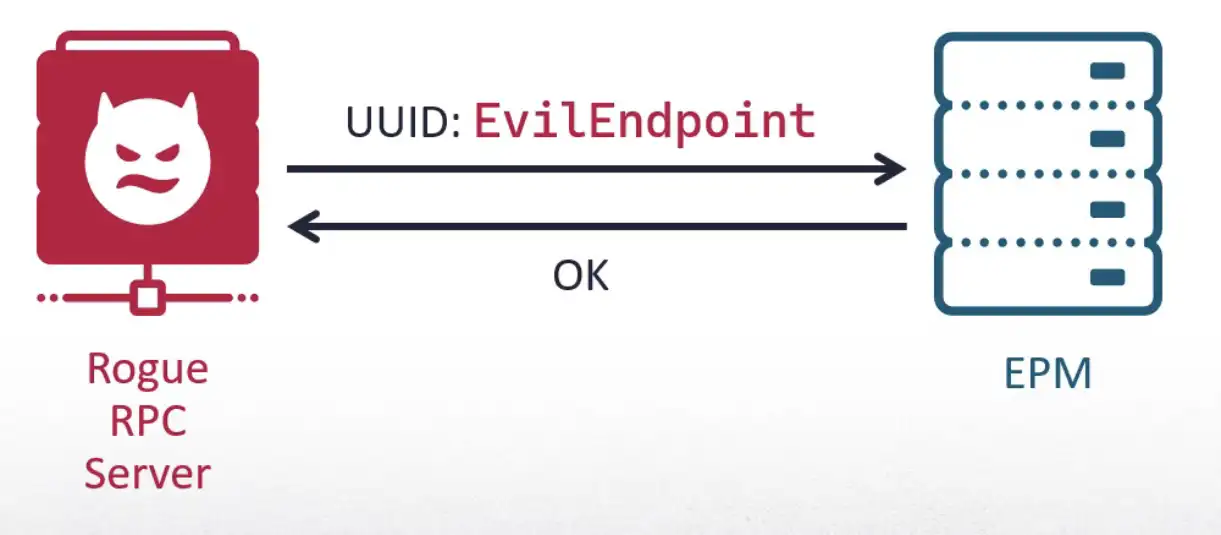

To begin, I needed to register with the EPM, which I could do with the RpcEpRegister API. But I didn’t want to just register any interface. I needed to behave like a known server and copy exactly what it does, which means registering its interface.

I anticipated battling with error codes and diving into security mitigations, but when I tried to register an interface that belonged to a built-in service, it just worked. Moreover, it didn’t even require admin privileges.

I was shocked to discover that nothing stopped me from registering known, built-in interfaces that belong to core services. I expected, for example, if Windows Defender had a unique identifier, no other process would be able to register it. But that was not the case.

However, even after achieving this, clients didn’t connect to me. I realized I didn’t receive a connection because the original service registered an endpoint to its interface before me. When I tried registering an interface of a service that was turned off, its client connected to me instead.

This finding was unbelievable—there were no security checks completed by the EPM. It connected clients to an unknown process that wasn’t even running with admin privileges. This proved not only that my novel technique of EPM poisoning was possible and could be used to destabilize the core of Microsoft RPC (MSRPC), but also that it didn’t even require me to have administrative privileges.

As far as I could tell, this was an attack vector that had never been explored before. Now, I would see if I could weaponize it.

Developing the RPC-Recon Tool

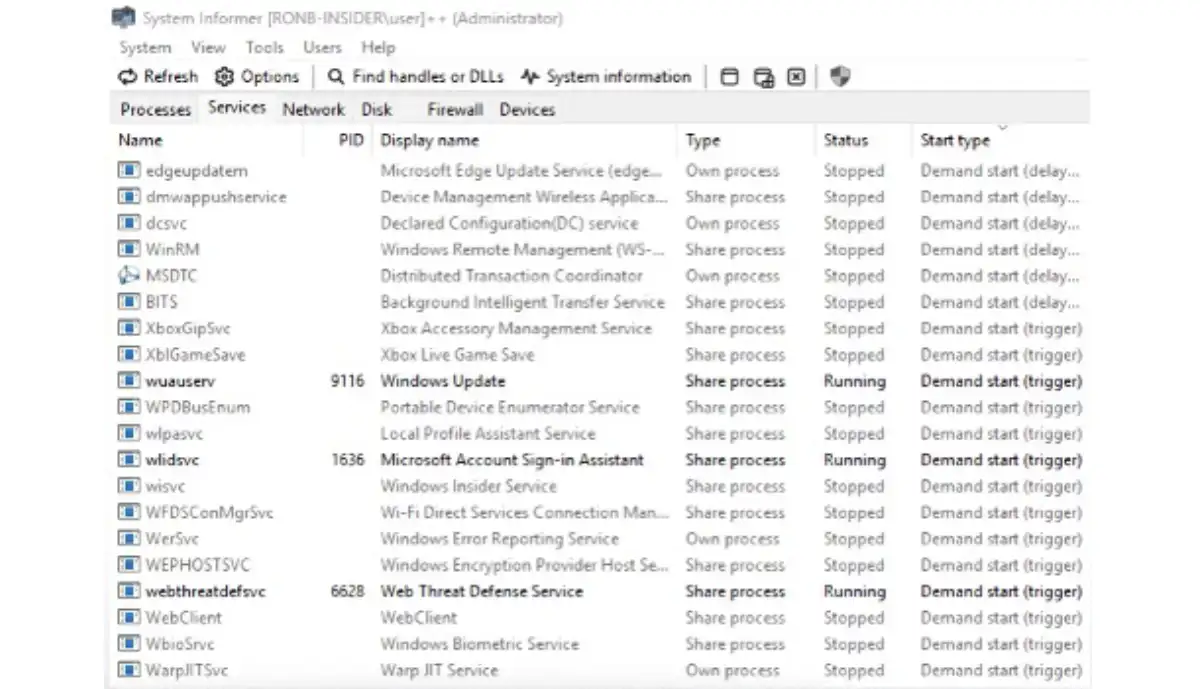

Now that I knew EPM poisoning was possible, it was time to gather data and find a candidate to create an attack with actual impact. I now knew that every RPC server that isn’t launched in boot could be prone to a hijack. Any service with a manual startup posed a security risk based on the fact that its RPC interface wouldn’t be registered on boot. The image below shows an example of the many services that could be vulnerable.

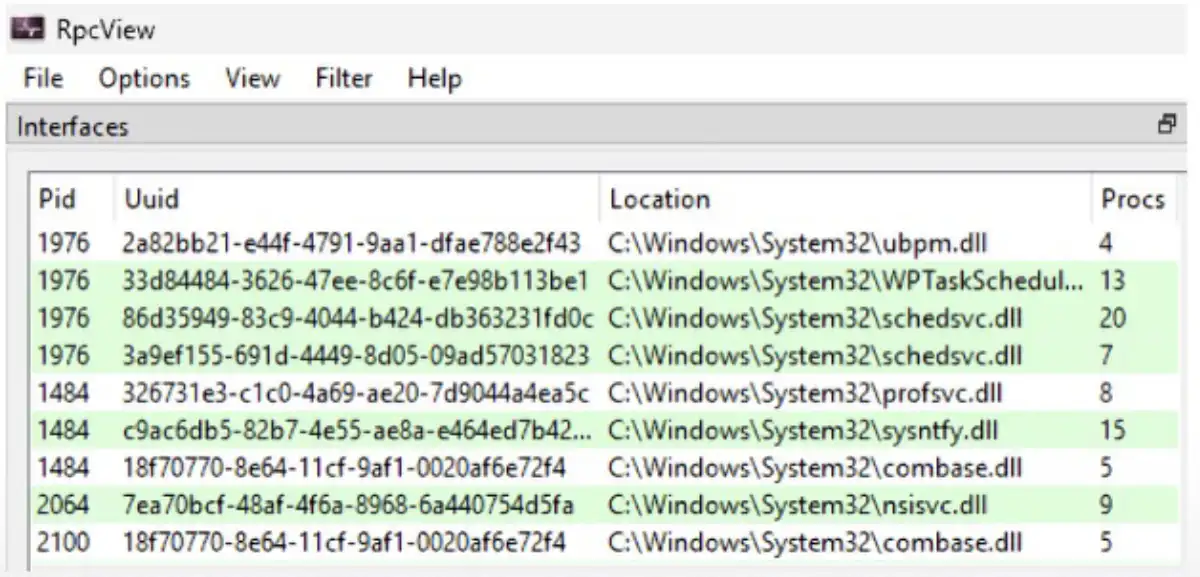

My next step was to gather a list of all the interfaces that aren’t mapped to an endpoint. As I mentioned before, dynamic endpoints can be retrieved from the EPM remotely or locally using WinAPI. To be thorough, I needed to also find the well-known endpoints. I used RpcView to scan the memory of every process, locate the module rpcrt4, and parse internal structures to list the information shown below.

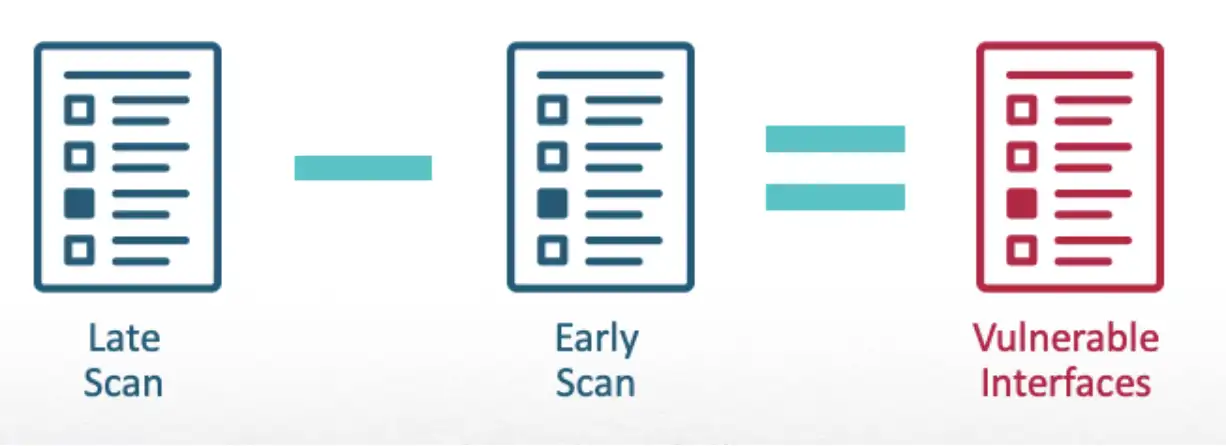

I needed a comprehensive tool that would know how to retrieve both types of endpoints, so I developed RPC-Recon. Its purpose was to find interfaces that could be registered right after the system boots, before most services are launched. It was designed to launch with a scheduled task when a user logs on, query the EPM, and scan the memory of processes. Then it would wait for several minutes until delayed services start. After that, it would perform the same retrieval again.

Finally, it would compare the results. The difference would show vulnerable interfaces that could be registered before the original service.

Since this tool is used for gathering information and not for the attack itself, I execute it with admin permissions, so it can scan the memory of elevated processes.

Demo

To see these capabilities in action, the following demo shows how RPC-Recon is executed with the flag /register to create a scheduled task that will execute with elevated privileges when I log on. After a restart to make sure most services aren’t running, the tool will scan the system twice and compare the results. After the comparison is made, it will show how I am able to get the log file of all the interfaces that registered late to develop a list of potential targets.

Launching a Rogue Server

After my initial surprise that I could register to the EPM with any interface I wanted, regardless of whether it was critical to the system functionality or belonged to a core component, I developed a generic RPC server that would register known interfaces and gather information on the clients connected to it.

As I started receiving connections from various processes on multiple interfaces, my server showed that those processes were services running as a system. I was sure I was about to achieve the easiest privilege escalation ever.

Leveraging the Connections

The most intuitive method to leverage the connection for privilege escalation is to call RpcImpersonateClient and spawn a new console without our token, but it failed. I was able to gain a new token, but creating a new process with it failed due to ERROR_BAD_IMPERSONATION_LEVEL. Apparently, there was a policy for impersonation scenarios that prevents medium integrity threads from impersonating a token with higher integrity.

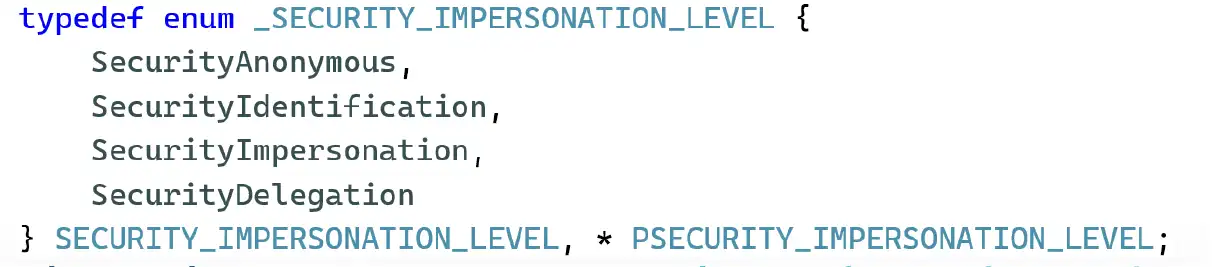

To understand this mechanism better, it’s helpful to first understand the meaning of each level, shown in the image below.

- The Anonymous level means the server cannot know who connected to it.

- The Identification level, which I received, lets the server query the client’s privileges and security identifier. It is used to check if the client is allowed to access certain resources.

- The Impersonation level is what I wished I had. It lets the server perform actions on the local machine with the client’s security context. If the client is more privileged than the server, the server can use the impersonation for privilege escalation.

- The Delegation level lets the server impersonate the client’s security context on remote systems.

This prompted another idea: could I leverage the connection for NT LAN Manager (NTLM) authentication? I tried to use my new token to authenticate against an SMB server that belonged to me. That would usually disclose the NTLM hash.

But again, the impersonation policy prevented it. To access remote resources over the network, I would need the highest impersonation level, which is delegation. At this point, it became clear that I couldn’t abuse the RPC connection.

Looking for Credentials

Next, I considered whether I could take advantage of the functionality the RPC server offers. If I masqueraded as a server used for authentication, the clients would provide me with sensitive credentials.

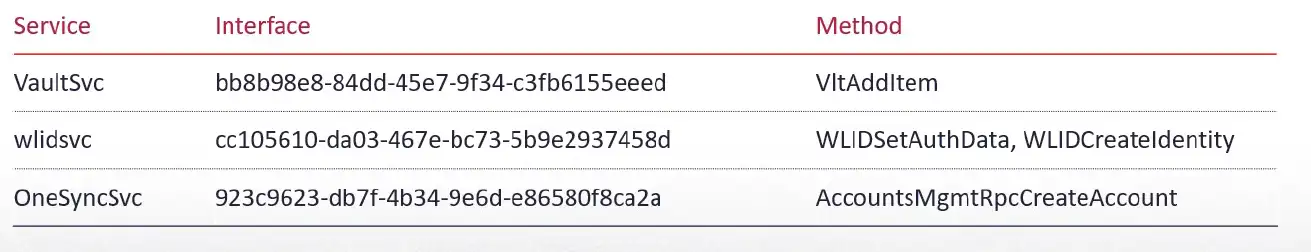

Out of all the vulnerable interfaces, I looked for ones with keywords like credentials, identity, and account. I ended up with the following three interfaces: the vault service, the Microsoft account sign-in assistant, and the sync host service.

However, when I launched my rogue server and used the clients, none of them connected to me. This is because of another security mechanism.

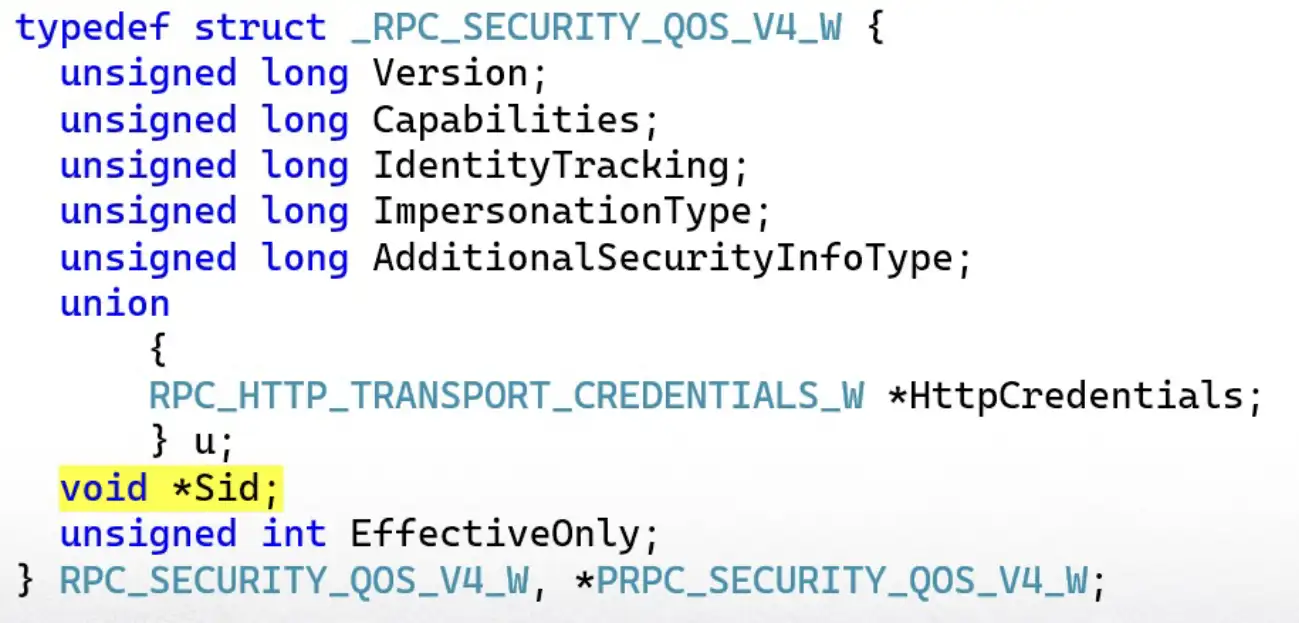

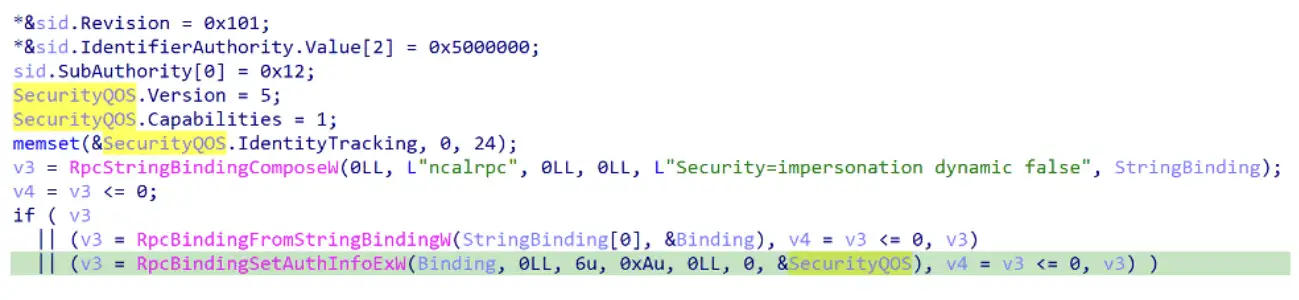

One of the properties a binding handler can have is security Quality of Service (QOS). If the client is expecting the server to run as NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM, it can specify its security identity and that will prevent a connection to a server running as another user. This is what the RPC clients did, which is why they didn’t connect to me.

For example, we can see the RPC client of the Microsoft account sign-in assistant creates a security QOS structure with the security identifier of the local system account, and then it applies it to the binding handle.

I knew EPM poisoning had potential, but I had to keep looking for the right way to abuse it.

Manipulating File Access

Another way to achieve privilege escalation is performing an action I wouldn’t be allowed to do natively, like writing to a system32 directory.

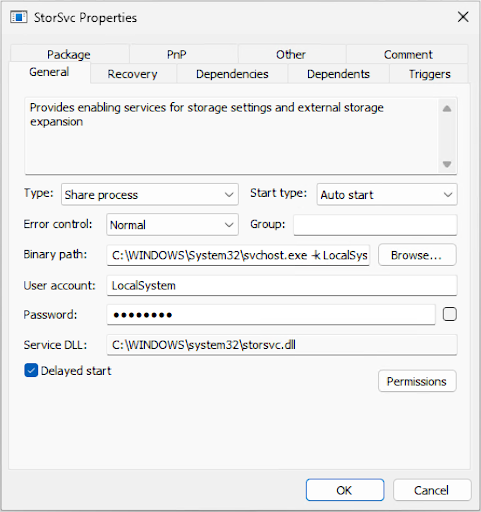

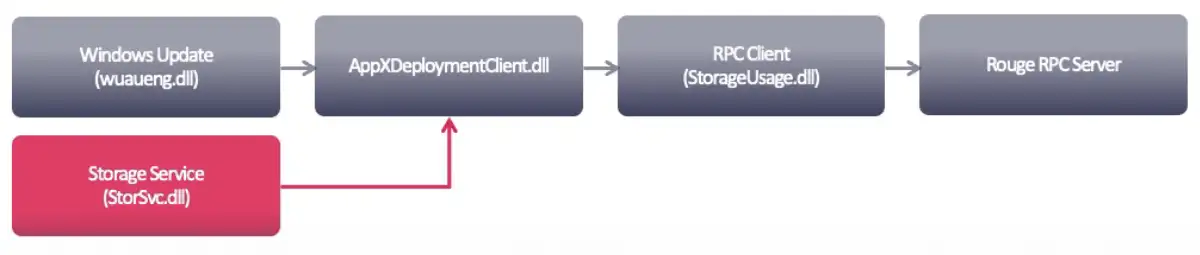

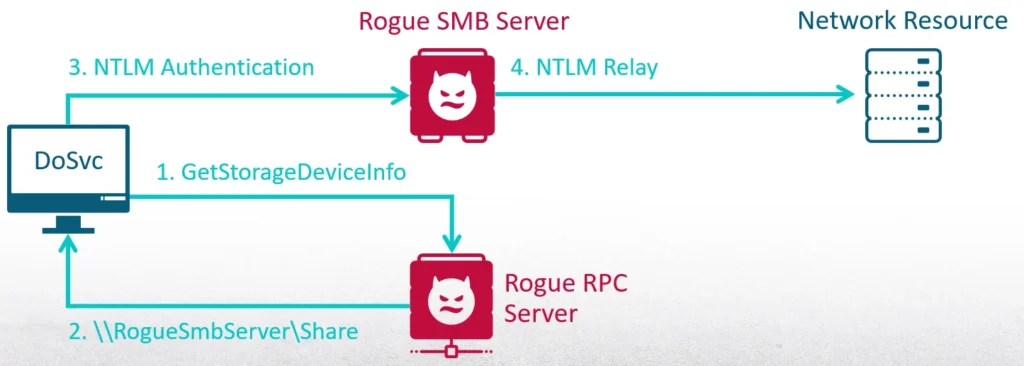

If I could masquerade as a file system service, another privileged service might ask me for data over a file that it would then copy somewhere. Looking through my victim’s list, I found the Storage Service. It is implemented in the file StorSvc.dll, and it is set to delayed start.

Next, I launched my rogue server again, but this time registered only the interface of the Storage Service. I then monitored the machine for RPC connections that happened naturally and gathered data on the clients of StorSvc.

The first service that connected to me? Windows Update—a highly privileged service in the operating system that can modify drivers and core DLL files. And it connected to an unknown process running with low privileges—a shocking security gap.

Next, I received a connection from Storage Service itself, which didn’t make sense, since I was pretending to be it. Apparently, this service uses its own RPC client to connect to itself. Since I registered the interface first, it connected to me.

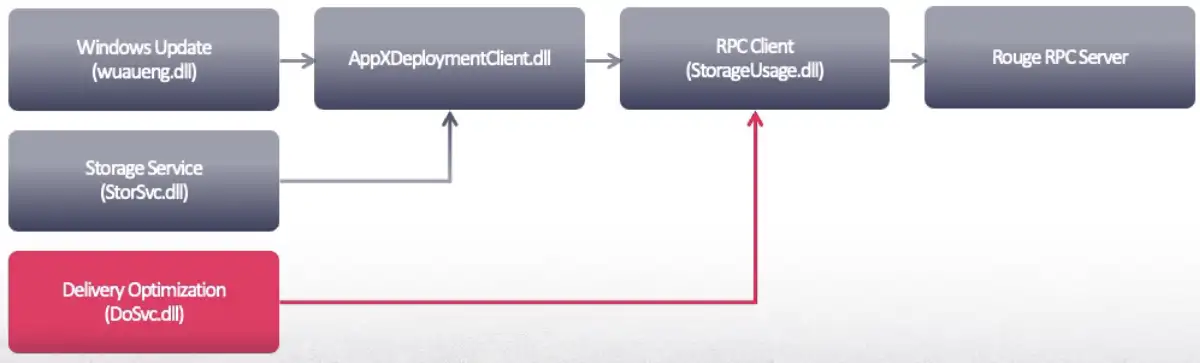

The last connection I received was from the Delivery Optimization service, which is responsible for downloading updates and packages from alternative sources to make distribution more efficient.

The Delivery Optimization service runs as a protected process light (PPL). Manipulating it proves that EPM poisoning indeed has a significant impact and that exploiting StorSvc is the right direction—even the most protected services would connect to me.

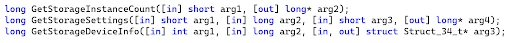

To manipulate the process, I needed to understand what it receives as input and what it is used for. Out of the 36 methods that the interface exposes, only three were invoked and all of them were undocumented. So, it was difficult to understand what they were used for. However, two of them returned an integer back to the client, which indicated they were unlikely to have a major impact. The third method, on the other hand, returned an undocumented structure. That had more potential.

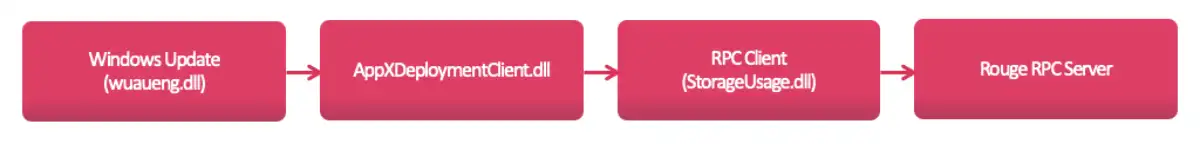

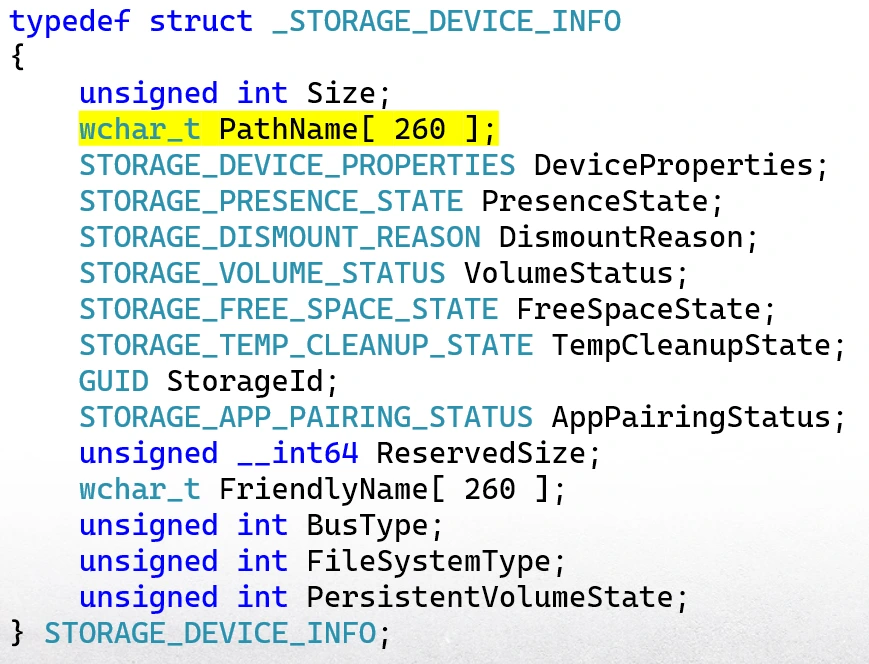

I needed to understand the definition of the structure returned by the method GetStorageDeviceInfo. One way to do that is to look at the functions on the client side that receive this struct. The call stack that led to the RPC call went through a DLL allied AppXDeploymentClient. When I disassembled it, I was surprised to see its public symbols contain a lot of information about the Storage Service interface. It had enums and variable names—basically everything I needed.

The best part was that it revealed that our struct contained a path. At this point, all I had to do was apply this definition on this assembly of the other clients to see what they were doing with this path.

After digging through this assembly of all the clients, I found out that the Delivery Optimization service performs a few sanity checks on the path it receives that I was able to bypass, and then it creates a directory based on that path. I’d finally found the action I could manipulate. Our low-privileged process could return a path that would be used by a high-privileged process.

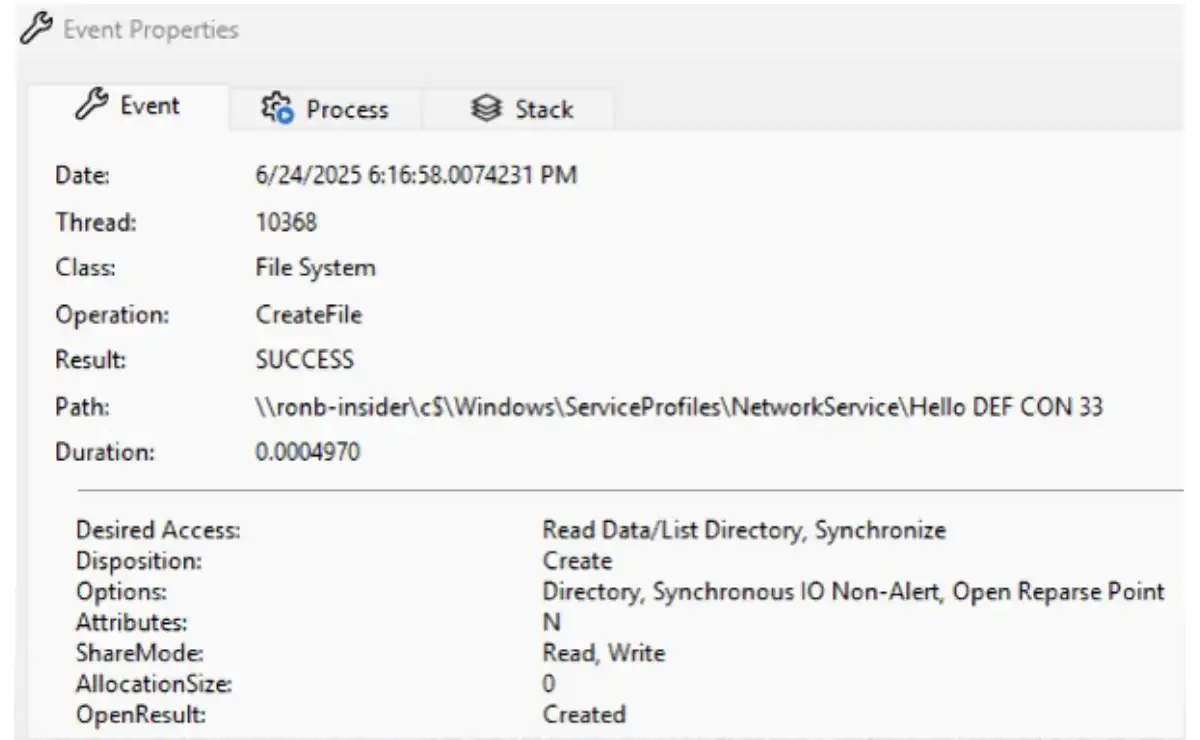

The Delivery Optimization service runs as the user NT AUTHORITY\NETWORK SERVICE. The easiest way to exploit this vulnerability was to create a directory in the home folder of this user—and it worked. I returned a network share of the local machine C: Drive to bypass the sanity checks and the directory “Hello DEF CON 33” was created, as shown below.

To see what else I could accomplish with vulnerability, I needed to understand more about this user and what it is used for.

Processes running as a network service have a token with a very high integrity level—the same as the local system accounts. But there is a difference between them. The user NT AUTHORITY\NETWORK SERVICE is not part of the administrator’s group. It means that it doesn’t have write access to most of the sensitive directories, registry keys, and processes on the machine. The purpose of this user is to have a few privileges locally, but to be able to authenticate remote machines. It does that using the machine account.

When a computer joins an active directory domain, an account is created in the NTDS database that represents that computer. This account can be easily identified by the dollar character at the end of its name. Like any domain user, it has a password, group memberships, and can be used to access resources in the domain network.

The machine account is often abused in penetration testing—depending on the configuration of the domain—and logged on users cannot authenticate to remote resources with those credentials. They are only used by the local system and network service accounts. That is where my vulnerability comes in. I could bypass the limitation applied on logged on users and authenticate with the machine account.

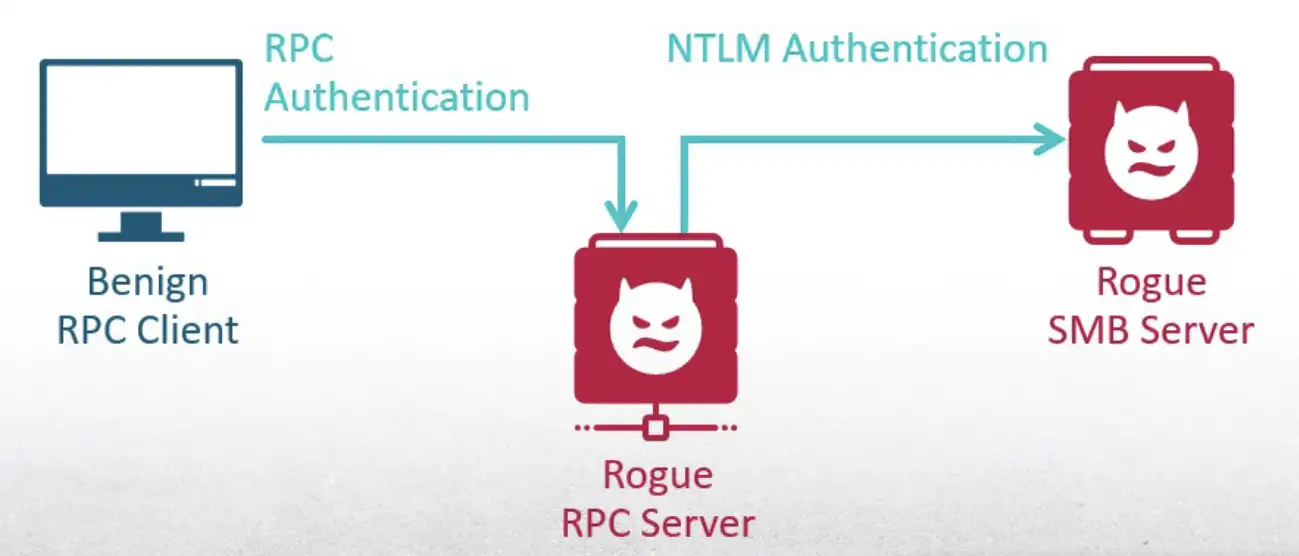

Previously, I showed how my RPC server returned a network share of the C: drive to the Delivery Optimization service. If I returned a network share of an external server, the service would authenticate against it with the machine account credentials. And I would be able to relay the NTLM authentication. I just successfully crossed the security boundary.

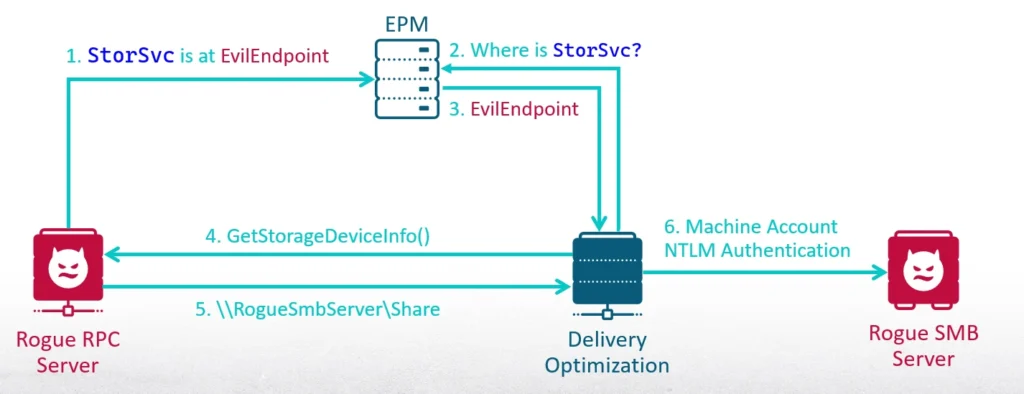

The Attack Flow Recap

As a medium integrity process, I can create a scheduled task that will be executed when the current user logs in. At this point, most of the RPC servers haven’t launched yet. My first step is to register the interface of the Storage Service. Then I will trigger the Delivery Optimization service to send an RPC request to the Storage Service. It connects to it with a dynamic endpoint, which means it will query the EPM and get the endpoint that I registered. Then it will invoke the method GetStorageDeviceInfo. In return, it will receive an SMB share to a server that I launched. The final step is the Delivery Optimization service authenticating to me with the machine account credentials—I then relay the authentication.

The RPC-Racer Tool

I developed a new tool called RPC-Racer to complete this attack. In addition to forcing the authentication of the machine account, RPC-Racer is designed to launch rogue RPC interfaces. It gathers information on the clients connected to it, which is useful for researching vulnerabilities in other servers.

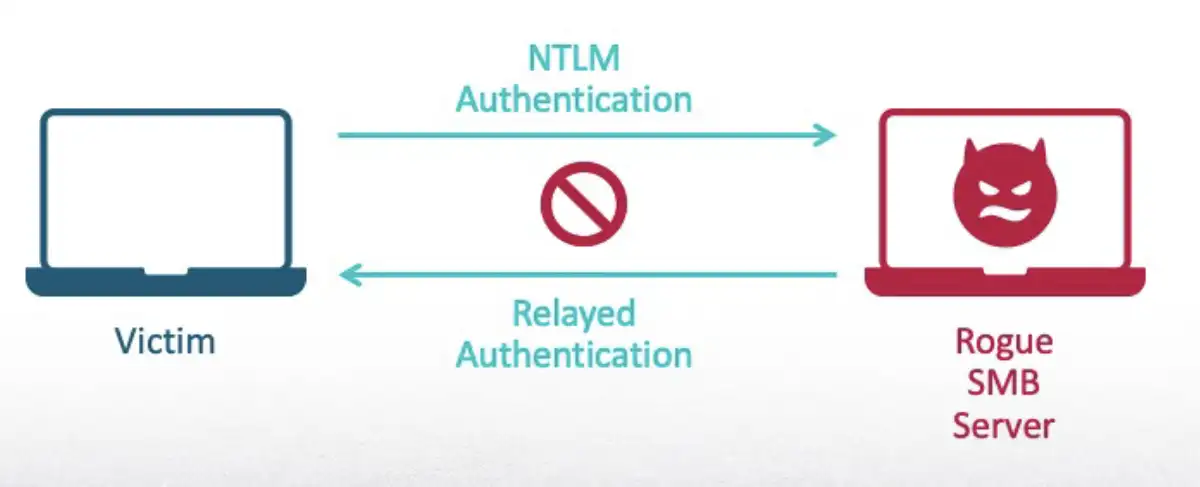

The starting point of this attack is running as a medium integrity process. If I could relay the machine account authentication back to the computer I was running on, I would be able to escalate my privileges. However, this is not possible due to a security mitigation. An NTLM authentication can’t be relayed back to the computer that originated it.

Therefore, I needed to find another server in the domain. To understand the impact of forcing and relaying a machine account authentication, I looked at the machine account of the domain controller (DC).

Employing an ESC8 Attack

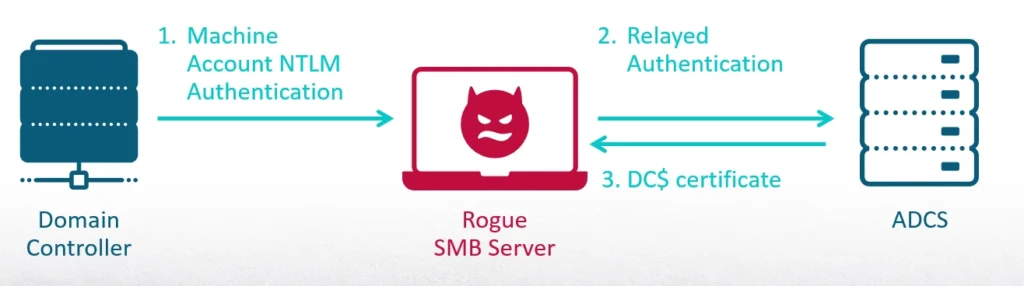

If I executed the RPC-Racer tool as a low-privileged user on the DC, I could use the authentication for an attack called ESC8. ESC8 is an attack that leverages the Active Directory Certificate Service (ADCS) for privilege escalation.

This server is part of the domain and the certificate it generates is recognized by other computers in the network. Also, those certificates can be used for authentication instead of plain text credentials. To be specific, ESC8 targets the web enrollment feature of ADCS.

This feature allows a user to log in to the web server managed by the ADCS and request to generate a certificate. What happens in ESC8 is that the attack relays an NTLM authentication to request a certificate from the web server that represents a privileged user in the domain.

Step 1: Requesting a Certificate for D$

Like I said before, NTLM authentication cannot be relayed back to the same computer. I want to use the privileges of the DC machine accounts, but I need another form of authentication.

The first step to achieve that is to relay the authentication created by RPC-Racer to the web server of ADCS. It generates a certificate for me that represents the machine account of the DC. This can be accomplished with the ntlmrelayx from Impacket.

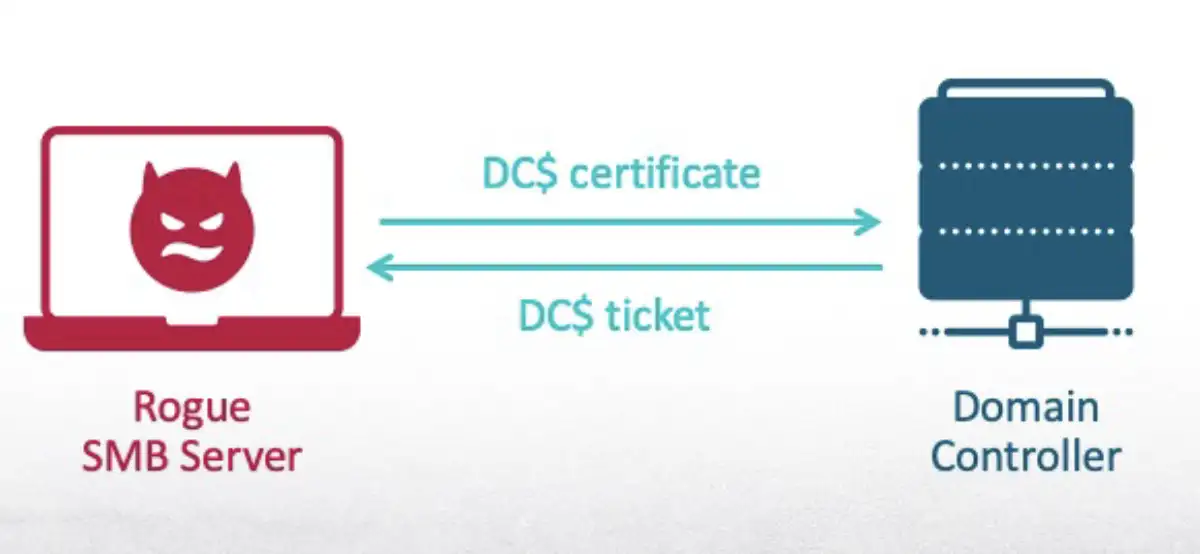

Step 2: Using the Certificate to Request TGT

I cannot authenticate anywhere across the domain with this certificate yet. The next step is to request a ticket granting tickets (TGT) from the DC. This is a legitimate Kerberos ticket that can be used to request access to resources in the domain. This is accomplished using the certipy tool.

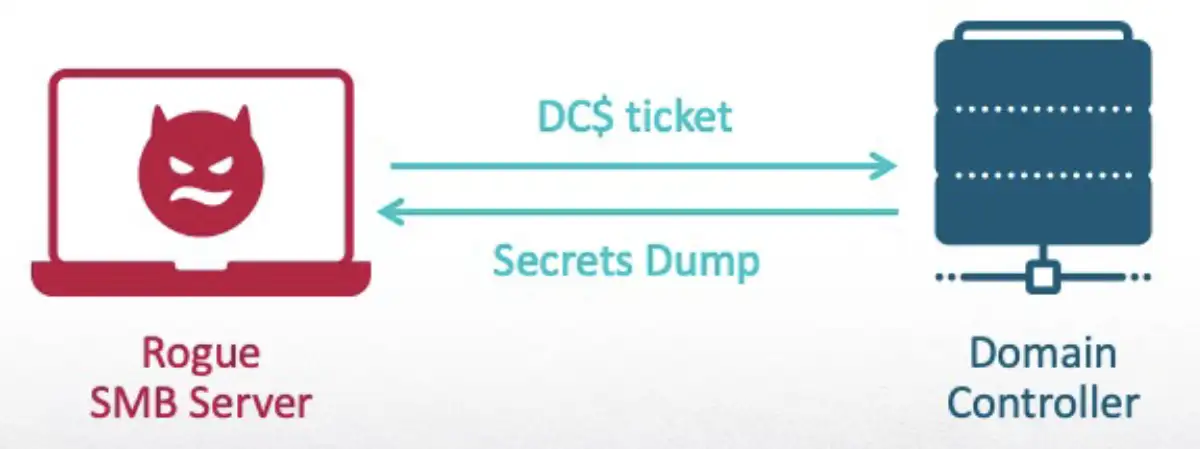

Once I had the TGT of the DC machine account, I could use it to execute several attacks. The most common would be to dump the password hashes of all the users in the domain. To accomplish this, I used Impacket again, but this time the secretsdump tool.

Demo

To see these capabilities in action, the following demo shows how I launched a rogue SMB server with ntlmrelayx and used it to relay the authentication to the ADCS. I then executed RPC-Racer as a low privileged user on the DC and showed how the Delivery Optimization service requested a path from me and my SMB server received the authentication. I then used certipy to request a TGT based on the certificate that was generated for me. Once I had a TGT of the machine account, I was able to dump all of the domain controller secrets.

Additional Implications

As I have shown here, EPM poisoning is a real attack. While I have shown one way to abuse it, there are ways to get even more out of it:

- Man in the Middle: I could perform a man-in-the-middle technique by forwarding the request I received to the original service and filtering out calls to hide my foothold in the machine.

- Denial of Service (DoS): I could cause DoS by registering many interfaces and denying the requests, disabling a lot of functionalities. Instead of terminating processes or spamming them with packets, I could also just register their RPC interface first.

- Steal Credentials: I noted a few services that might be exploited for credential stealing, but there are probably even more.

Vendor Response

When it comes to our original research, SafeBreach is deeply committed to responsible disclosure. In line with that commitment, I notified Microsoft of my research findings in March 2025 and they assigned CVE-2025-49760 for the vulnerability I reported.

A patch for this vulnerability was released on July 8, 2025. The fix was made in the RPC client StorageUsage.dll to improve how the binding is made. Instead of creating a simple binding handle, a security QOS was applied to it. Now, the RPC connection is only made if the RPC server is running as the local system account.

Detection Capabilities

Since the patch specifically addressed the RPC client of Storage Service, there are many other clients and interfaces that are likely vulnerable to EPM poisoning. There are steps that can be taken to help detect this type of attack:

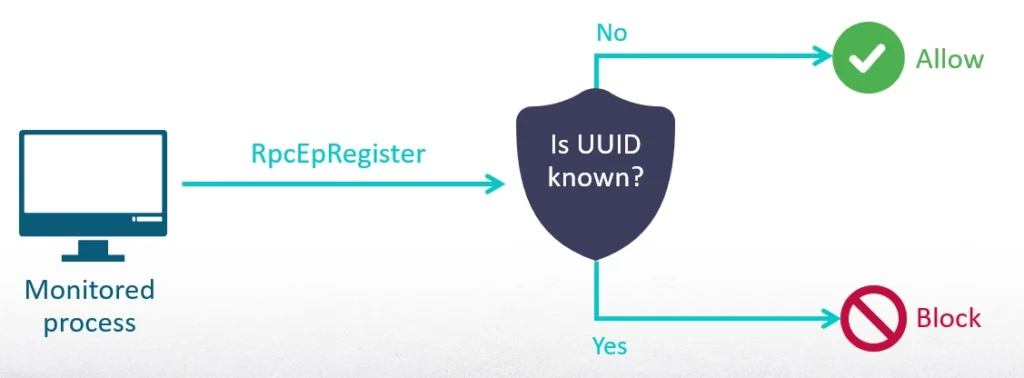

- Security products can use hooking and monitor calls to RpcEpRegister. If a process wants to register a known, built-in interface to the EPM and it isn’t a legitimate service, it should be detected.

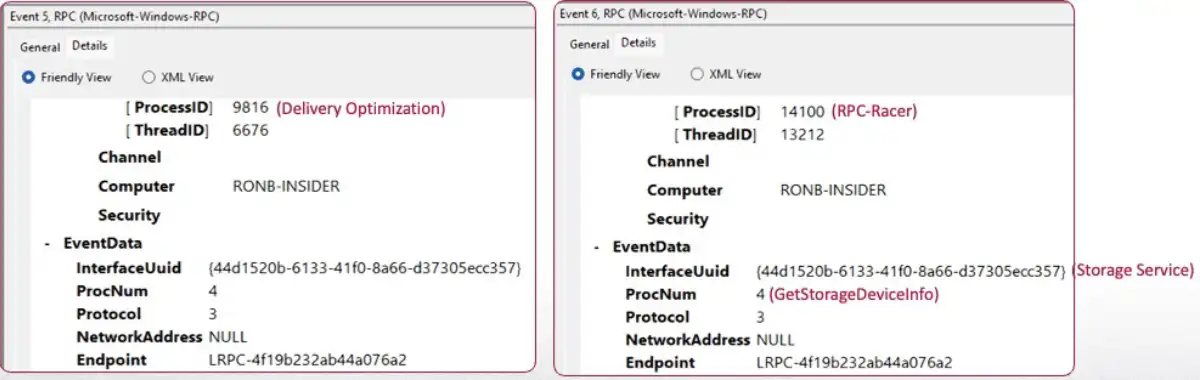

- Event Tracing for Windows can also be used. The operating system automatically generates events for many actions that occur on the machine. The provider named Microsoft-Windows-RPC logs a lot of useful information for this case. In these events, as shown below, we can see a correlation between the process ID of RPC-Racer, the process ID of the Delivery Optimization service, and the interface of Storage Service that I hijacked. We can even see the exact procedure number that was invoked, which correlates to GetStorageDeviceInfo. These event types can be used to detect cases of EPM poisoning. An unknown process received an RPC connection on a known interface.

Further Research

While I exploited the vulnerability I found to force the authentication of the machine accounts, I think there is potential for an even stronger impact by exploiting the same vulnerability differently.

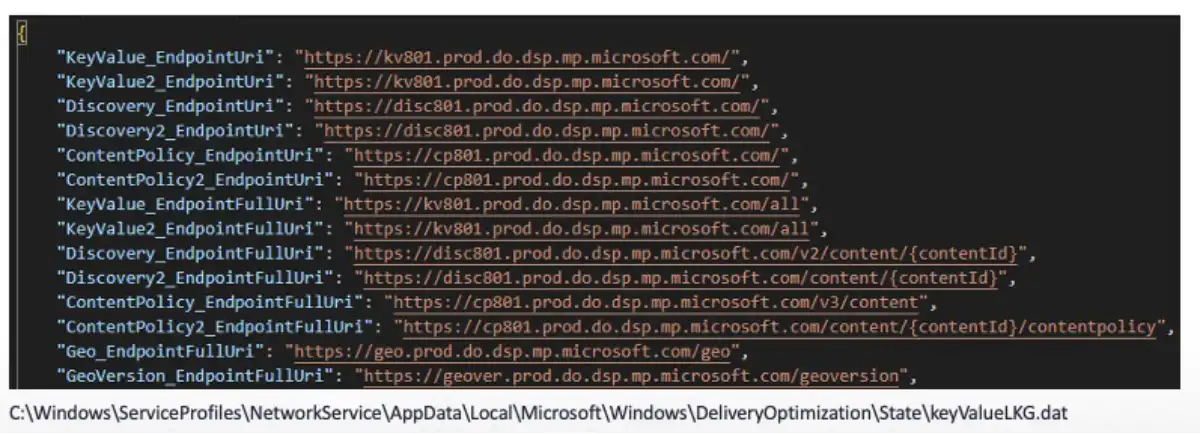

For example, the path I returned to the Delivery Optimization service is used as the private folder of the service where it will look for config files. This means that I could point it to a directory with poisoned configs that would affect the behavior of the service even more.

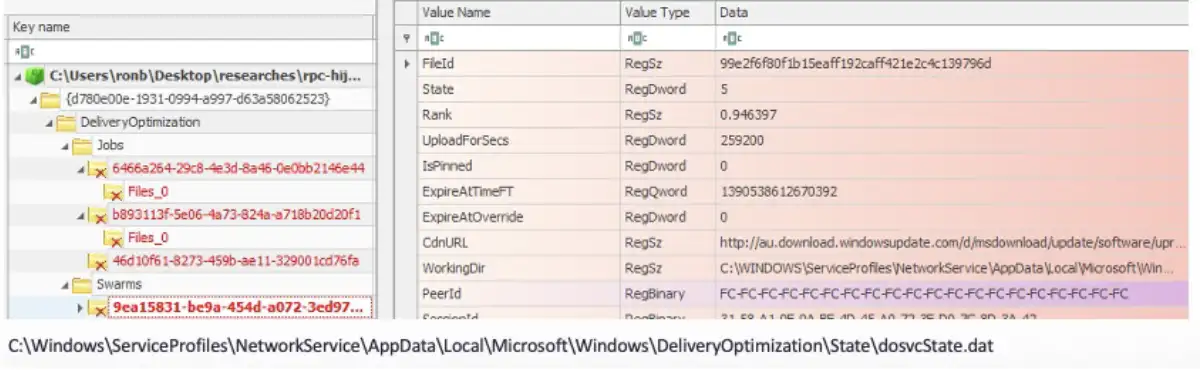

One of the config files is KeyValueLKG.dat. It contains many URLs. Another interesting config file is dosvcState.dat. This is a standalone registry hive used to manage the jobs assigned to the Delivery Optimization service. There are some values that definitely catch the eye, such as CdnURL and working directory. Creating a key with certain values might result in the service downloading files to protected directories.

And of course, the most prominent attack vector for further research would be to find more vulnerable RPC servers. This research has just scratched the surface—I believe there are so many more. For example, the Windows Security Center is vulnerable to EPM poisoning and Windows Defender interacts with it. Maybe it is possible to neutralize Defender by sending back a malicious response.

Conclusion

This research presented a serious security issue in a core component of the RPC protocol, namely that there is no verification process for registering interfaces that will be used by crucial services of the operating system. I showed how it was possible to map vulnerable RPC servers and then analyze and exploit the clients to achieve a potentially devastating result.

To help mitigate the potential impact of the vulnerabilities identified by this research, I have:

- Responsibly disclosed our research findings to Microsoft in March 2025, as noted above. All users should apply the patch provided by Microsoft in response.

- Provided several suggestions about detection capabilities organizations can enact to protect other clients and interfaces that may be vulnerable to EPM poisoning.

- Shared my research openly with the broader security community here and at my DEF CON 33 (2025) presentation to enable the organizations and end-users leveraging the Windows OS to better understand the risks associated with these vulnerabilities.

- Provided a GitHub research repository that includes the tools and exploits discussed within this research to serve as a basis for further research and development.

- Added original attack content to the SafeBreach platform that enables our customers to validate their environment against the EPM poisoning technique outlined in this research to significantly mitigate their risk.

For more in-depth information about this research, please:

- Contact your customer success representative if you are a current SafeBreach customer

- Schedule a one-on-one discussion with a SafeBreach expert

- Contact Kesselring PR for media inquiries

About the Researcher

Ron Ben Yizhak (@RonB_Y) is a security researcher at SafeBreach with 10 years of experience. He works in vulnerability research and has knowledge in forensic investigations, malware analysis, and reverse engineering. Ron previously worked in the development of security products and has been invited to share his research at DEF CON several times